The girls enjoying their new paint set, courtesy of aunt and uncle

The girls enjoying their new paint set, courtesy of aunt and uncle

Kevin J. Vanhoozer, on what the “mind of Christ” actually is:

The “mind of Christ” refers not merely to Jesus' intellectual quotient or his stock of knowledge but to his habitus: the distinctive pattern of all his intentional acts—desires, hopes, beliefs, volitions, emotions, as well as thoughts. The mind of Christ refers, in a word, to the characteristics pattern of Jesus' judgments—to the way that Jesus processes information and to the product of that process: the embodied wisdom of God. The mind of Christ is the set of moral, intellectual, and spiritual habits or virtues that serve as the mainspring for all the particular things that Jesus does and says.

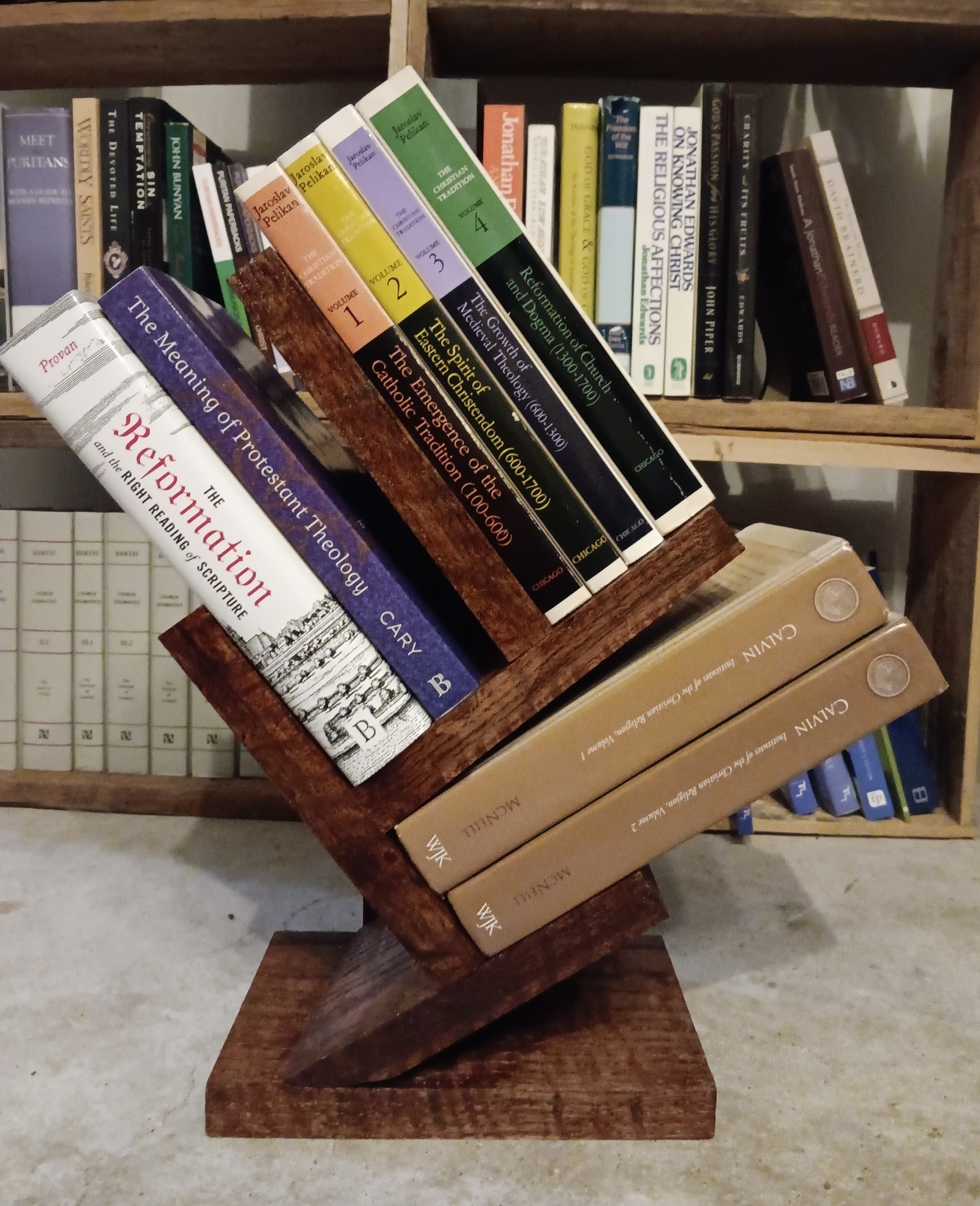

My Christmas gift to the bro-in-law:

Pictured here with books:

A denial of the past, superficially progressive and optimistic, proves on closer analysis to embody the despair of a society that cannot face the future.

Currently reading: The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in An Age of Diminishing Expectations by Christopher Lasch 📚

First time listening to Radiohead in a whiiiiiile

Finished reading: The Stoic Challenge: A Philosopher’s Guide to Becoming Tougher, Calmer, and More Resilient by William B. Irvine 📚

I’m not a Stoic, but I appreciate some of the their wisdom. Irvine’s book convinced me that I’m not as tough or resilient as I ought to be. Hopefully I can implement some of his strategies to good effect.

Finished reading: The Abolition of Man by C. S. Lewis 📚

My trek through Lewis' corpus continues. Next up: his fiction (Narnia, Space Trilogy, Till We Have Faces) and essays (God in the Dock, etc.).

Currently reading: The Stoic Challenge: A Philosopher’s Guide to Becoming Tougher, Calmer, and More Resilient by William B. Irvine 📚