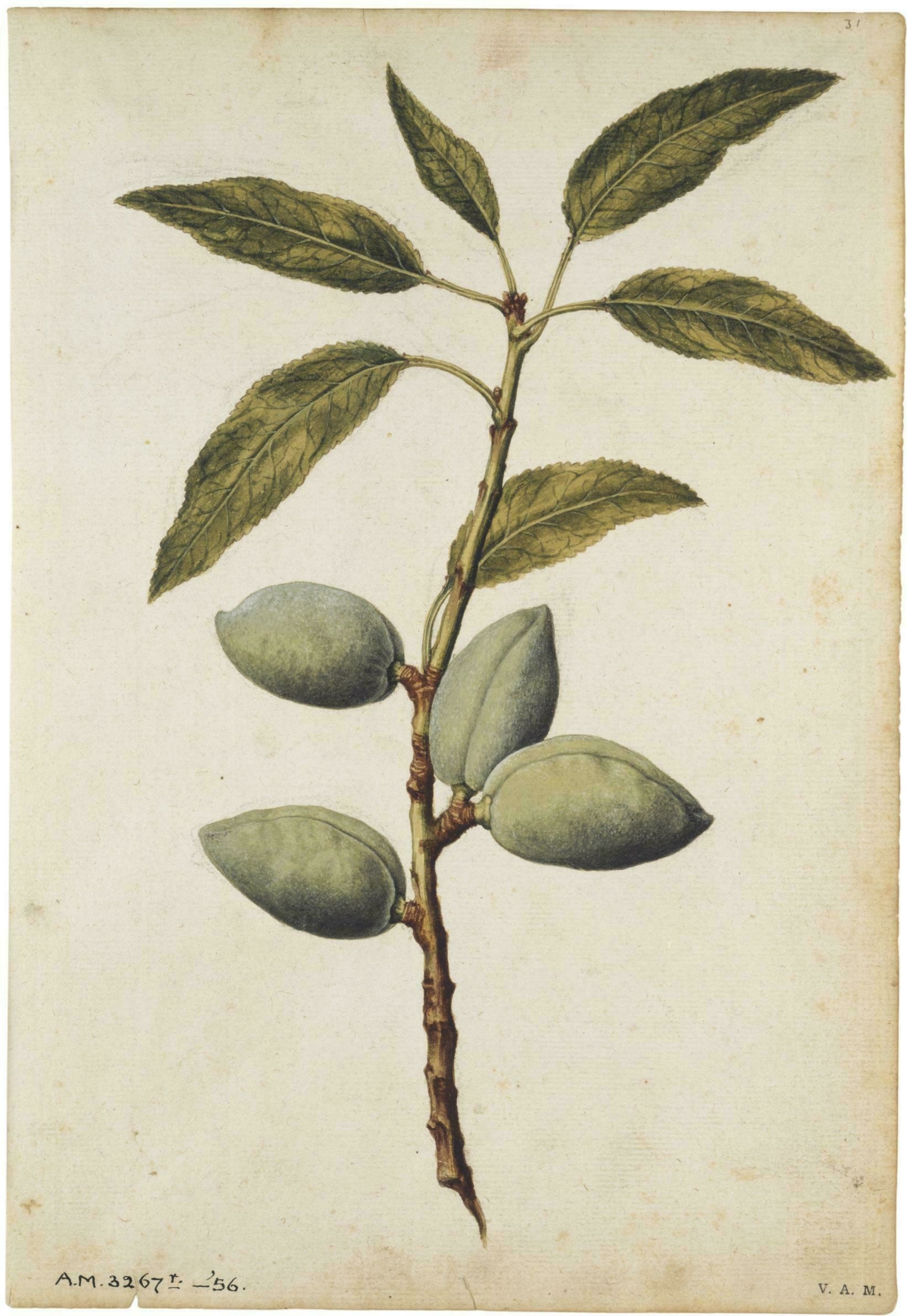

Exquisite botanical paintings from Jacques le Moyne, a sixteenth century French painter who is best-known for his work as part of a (failed) French expedition to Florida:

Finished reading: Grief Observed by C. S. Lewis 📚

Honest, sobering reflections on life without H. It’s Lewis, ergo worthwhile. But felt a little strange to read, as if I’d stolen his diary.

Sometimes, Lord, one is tempted to say that if you wanted us to behave like the lilies of the field you might have given us an organization more like theirs. But that, I suppose, is just your grand experiment. Or no; not an experiment, for you have no need to find things out. Rather your grand enterprise. To make an organism which is also a spirit; to make that terrible oxymoron, a ‘spiritual animal.’ To take a poor primate, a beast with nerve-endings all over it, a creature with a stomach that wants to be filled, a breeding animal that wants its mate, and say, ‘Now get on with it. Become a god.’

Five senses; an incurably abstract intellect; a haphazardly selective memory; a set of preconceptions and assumptions so numerous that I can never examine more than a minority of them—never become even conscious of them all. How much of total reality can such an apparatus let through?

Saw Ridley Scott’s Napoleon tonight with Kristyn. The battle sequences are certainly exhilarating (though the brutality of that style of warfare makes me borderline nauseous). Overall, an entertaining film, but I left feeling a little let down. Phoenix’s performance seemed a bit of a rehash of previous characters. Also, Napoleon’s motivations remained opaque to me throughout. For a character study, Napoleon didn’t help me get inside the head of this complicated figure.

Finished reading: Reading the Gospels Wisely by Jonathan T. Pennington 📚

A superb book. Pennington offers much sage advice on reading the gospels well and, in the process, he sparks in you a desire to read the gospels afresh (which is always a good sign with books on Holy Scripture).

Marseille (1954) by Nicolas de Staël: