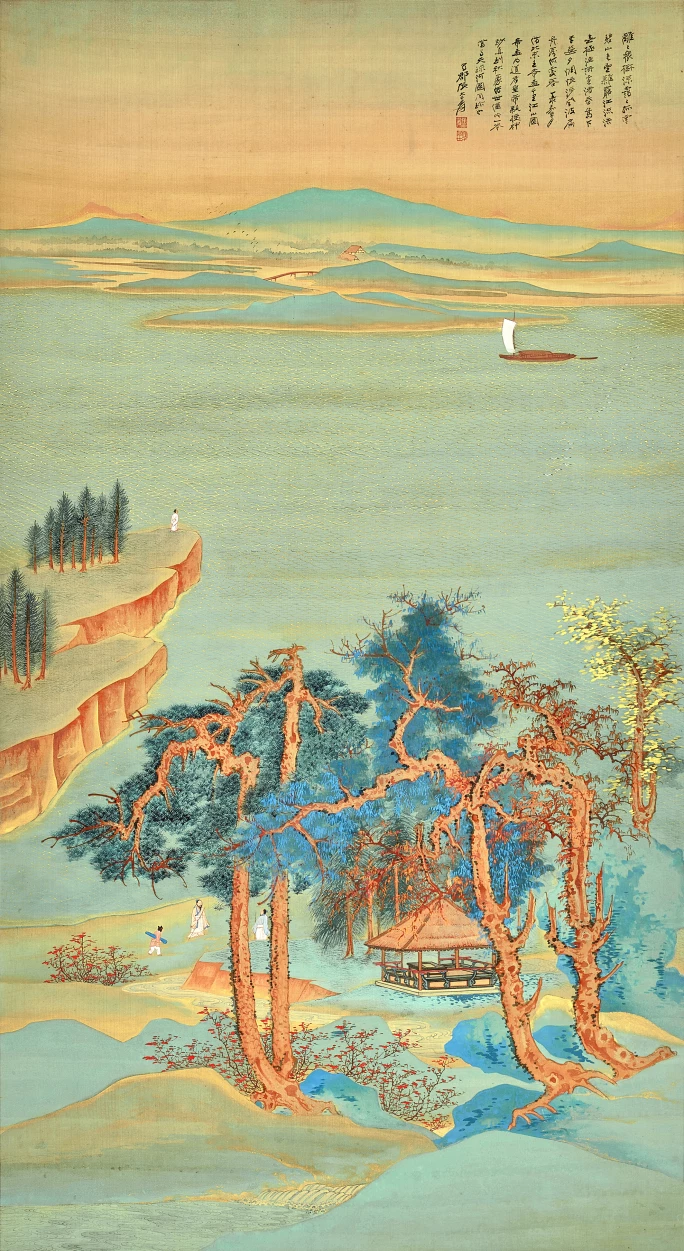

Landscape after Wang Ximeng (1948) by Zhang Daqian (his rendition of Wang Ximeng’s A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains):

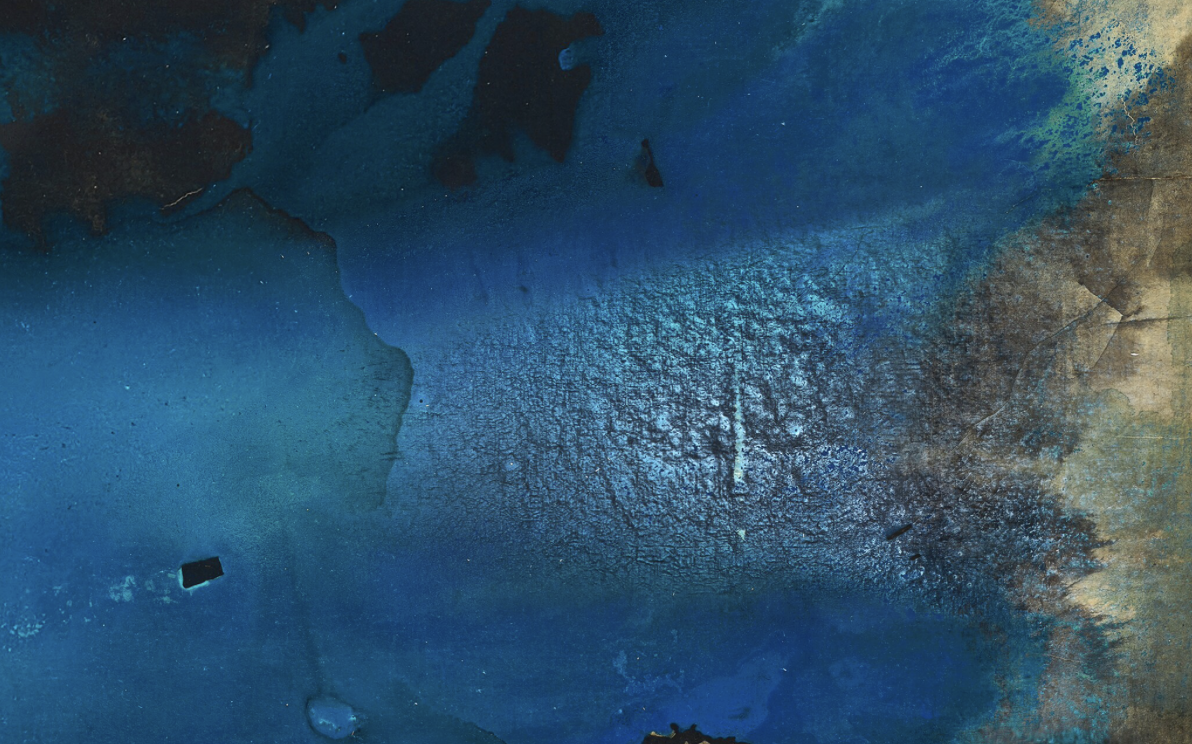

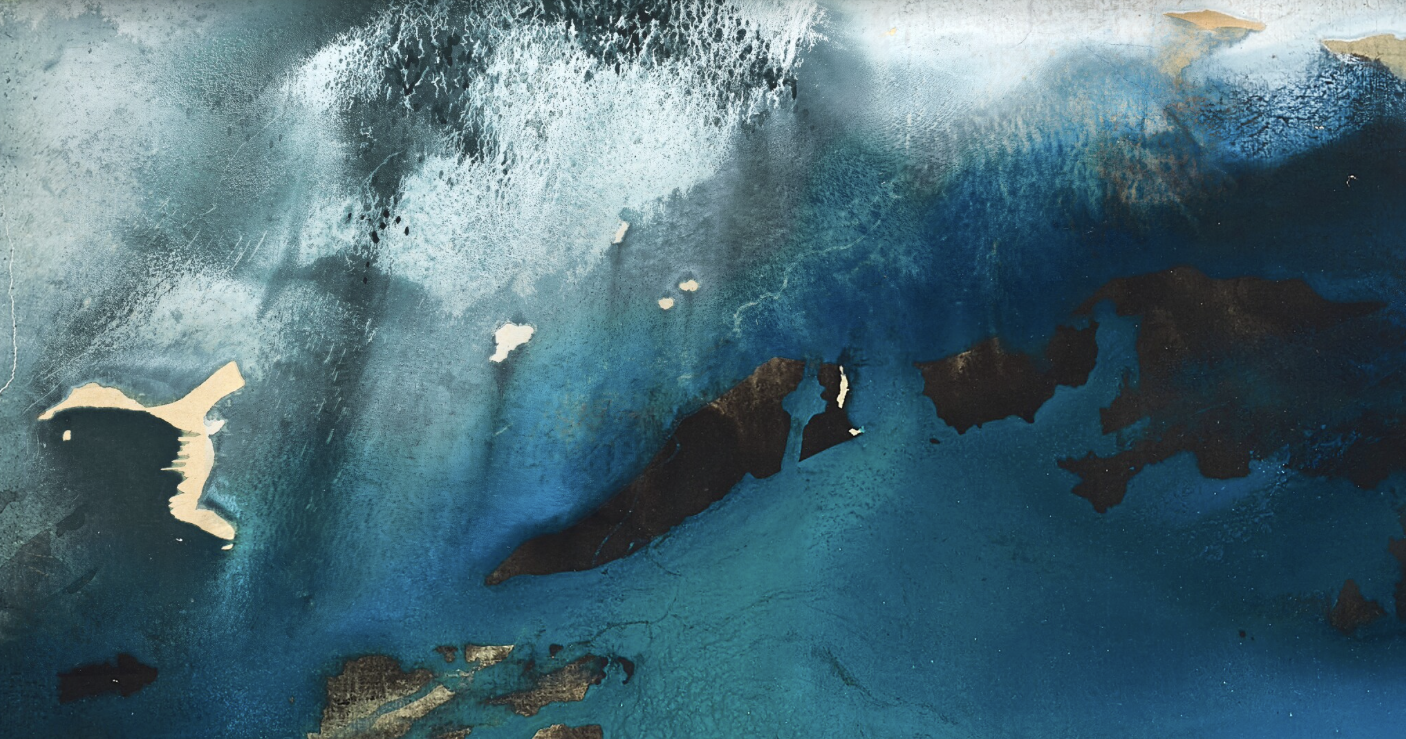

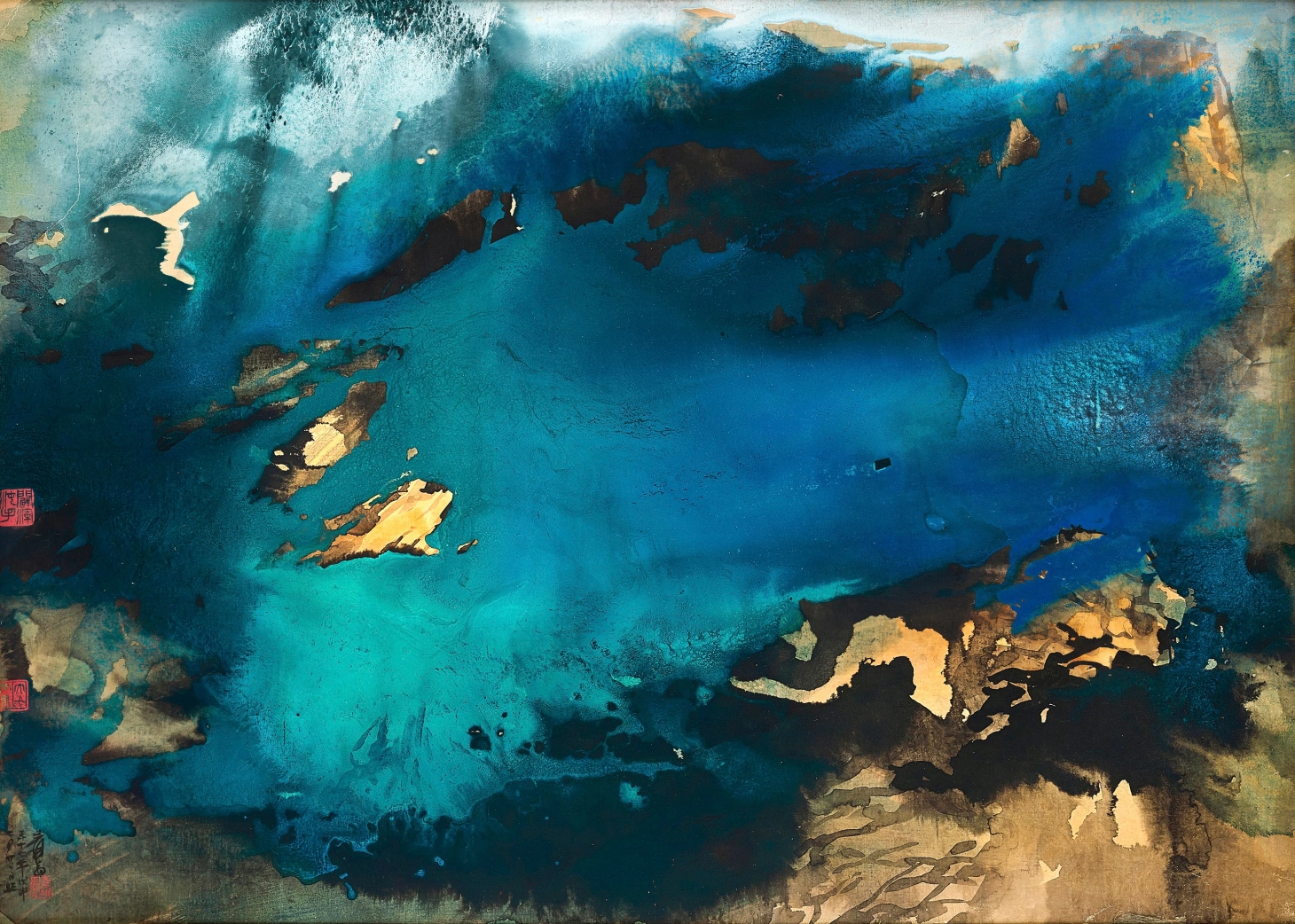

Mist at Dawn (1968) by Zhang Daqian:

Phil Christman, with a wonderful description of teaching (I’ll be filing away the phrase “heresy of paraphrase” for later):

For teaching always does feel somewhat false, somewhat incomplete. In the classroom, I take things I love and adapt them. I abridge them. I simplify. I commit the heresy of paraphrase. I make comparisons and explanatory analogies at which specialists would wince. I make reading lists, which always leave somebody important out—whether I cut Thoreau to make room for Harriet Jacobs (a stunningly vivid and economical writer) or the other way around. I find the right level of oversimplification for my audience, I go directly to it, and then, by degrees, I retreat from it, inviting students to follow me into greater complexity. I never stop worrying that I have replaced my subject with a slightly stupider changeling. It just goes with the territory.

We are Americans; our national myth is Footloose. None of us can enjoy our pleasures till we think someone wants us not to have them.