Poplars on the River Epte (1891) by Claude Monet:

Poplars on the River Epte (1891) by Claude Monet:

Three Trees in Grey Weather (1891) by Claude Monet:

Poplars in the Sun (1891) by Claude Monet:

Poplars (Wind effect) (1891) by Claude Monet:

Three Poplar Trees in the Autumn (1891) by Claude Monet:

Poplars (Autumn) (1891) by Claude Monet:

Poplars at Giverny, Sunrise (1891) by Claude Monet:

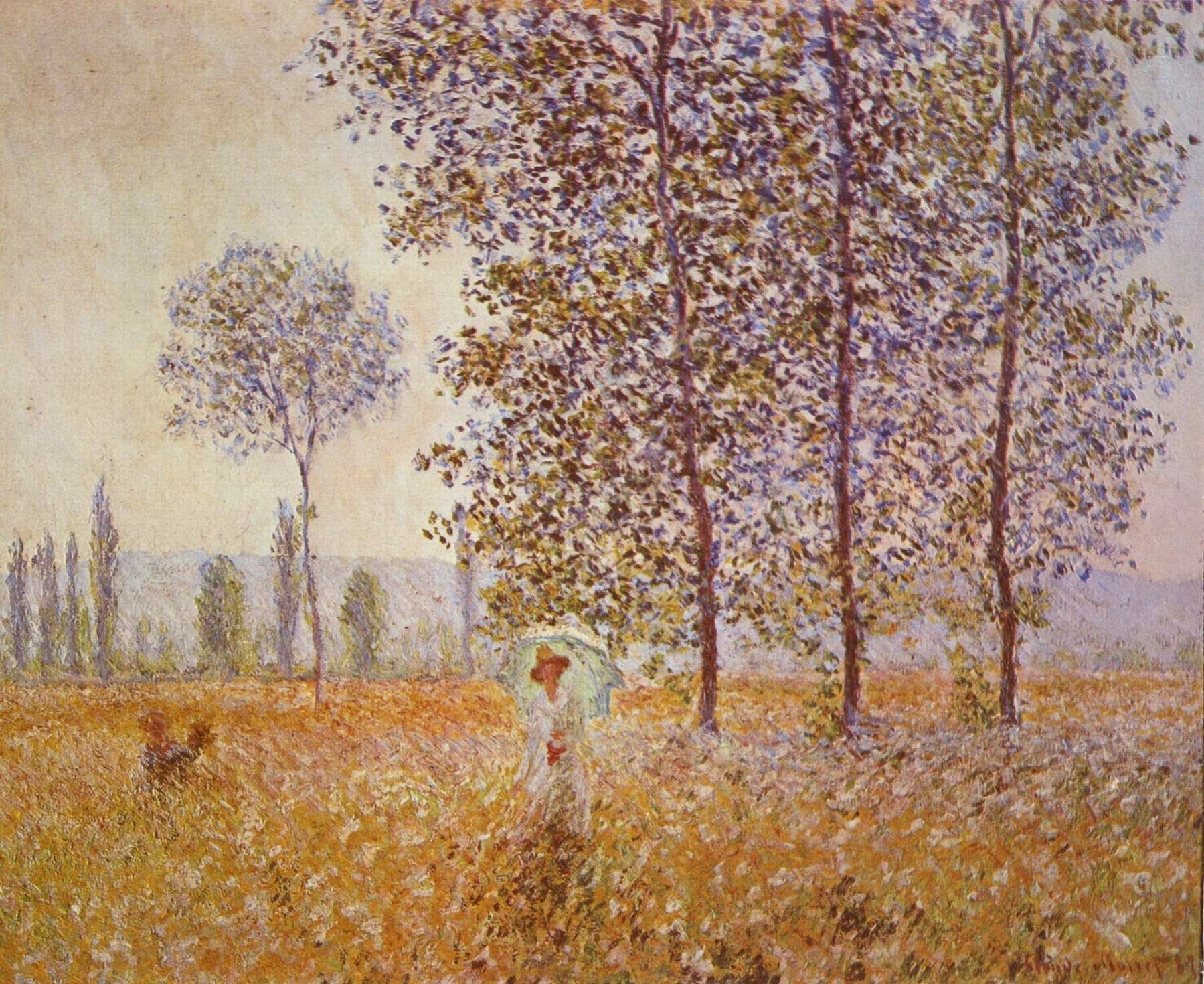

Poplars in the Sun (1891) by Claude Monet:

The Four Trees (1891) by Claude Monet:

Matthew Crawford (in a comment on Substack):

Apprenticeship is dismissed as being too narrow an education; what is wanted is workers who are flexible and ready to reinvent themselves at any time. But when you go deep into some art or skill, it trains your powers of perception. One becomes more discerning about this particular class of objects or problems. If all goes well, you get initiated into an ethic of caring about what you are doing, usually by the example of some mentor who exemplifies that spirit of craftsmanship. You hear the disgust in his voice as he surveys something done shoddy, or quiet admiration. What I mean to say is that technical education, though narrow in its immediate application, can be understood as part of education in the broadest sense: intellectual and moral formation. And…it offers a crucial counterpoint to the virtual.