Currently reading: A Spirituality of Fundraising (Henri Nouwen Spirituality) by Henri J.M. Nouwen 📚

Currently reading: A Spirituality of Fundraising (Henri Nouwen Spirituality) by Henri J.M. Nouwen 📚

Modern society has achieved unprecedented rates of formal literacy, but at the same time it has produced new forms of illiteracy. People increasingly find themselves unable to use language with ease and precision, to recall the basic facts of their country’s history, to make logical deductions, to understand any but the most rudimentary written texts, or even to grasp their constitutional rights. The conversion of popular traditions of self-reliance into esoteric knowledge administered by experts encourages a belief that ordinary competence in almost any field, even the art of self-government, lies beyond reach of the layman.

C. S. Lewis, replying to the charge that he doesn’t ‘care much for’ the Sermon on the Mount:

As to ‘caring for’ the Sermon on the Mount, if ‘caring for’ here means ‘liking’ or enjoying, I suppose no one ‘cares for’ it. Who can like being knocked flat on his face by a sledge-hammer? I can hardly imagine a more deadly spiritual condition than that of the man who can read that passage with tranquil pleasure. This is indeed to be ‘at ease in Zion’. Such a man is not yet ripe for the Bible.

The White Bridge (c. 1875-1890) by John Henry Twachtman:

Wild Cherry Tree (c. 1901) by John Henry Twachtman:

In all true Christian asceticism, [there is] respect for the thing rejected which, I think, we never find in pagan asceticism. Marriage is good, though not for me; wine is good, though I must not drink it; feasts are good, though today we fast.

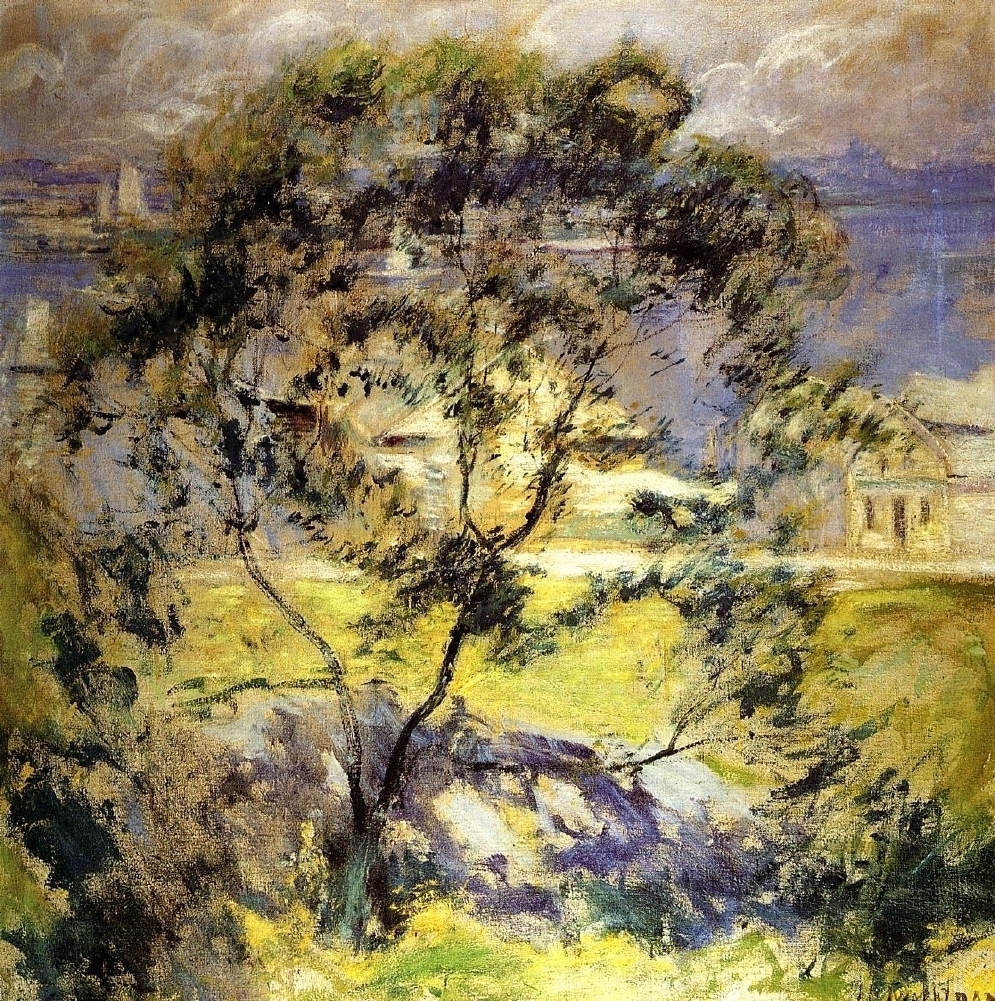

Valley in the Mountains (c. 1930s) by Louis Hovey Sharp:

Pasadena Light by Louis Hovey Sharp: