Currently reading: Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work by Matthew B. Crawford 📚

Currently reading: Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry Into the Value of Work by Matthew B. Crawford 📚

Finished reading: People Skills by Robert Bolton 📚

Lots of common sense wisdom about listening, asserting, and conflict resolution. Wish I would’ve read this a long time ago.

Grabbed coffee this afternoon with an old friend at Houndstooth in the Domain and spent the better part of the hangout discussing Ecclesiocentric Postliberalism. Time well spent in my book.

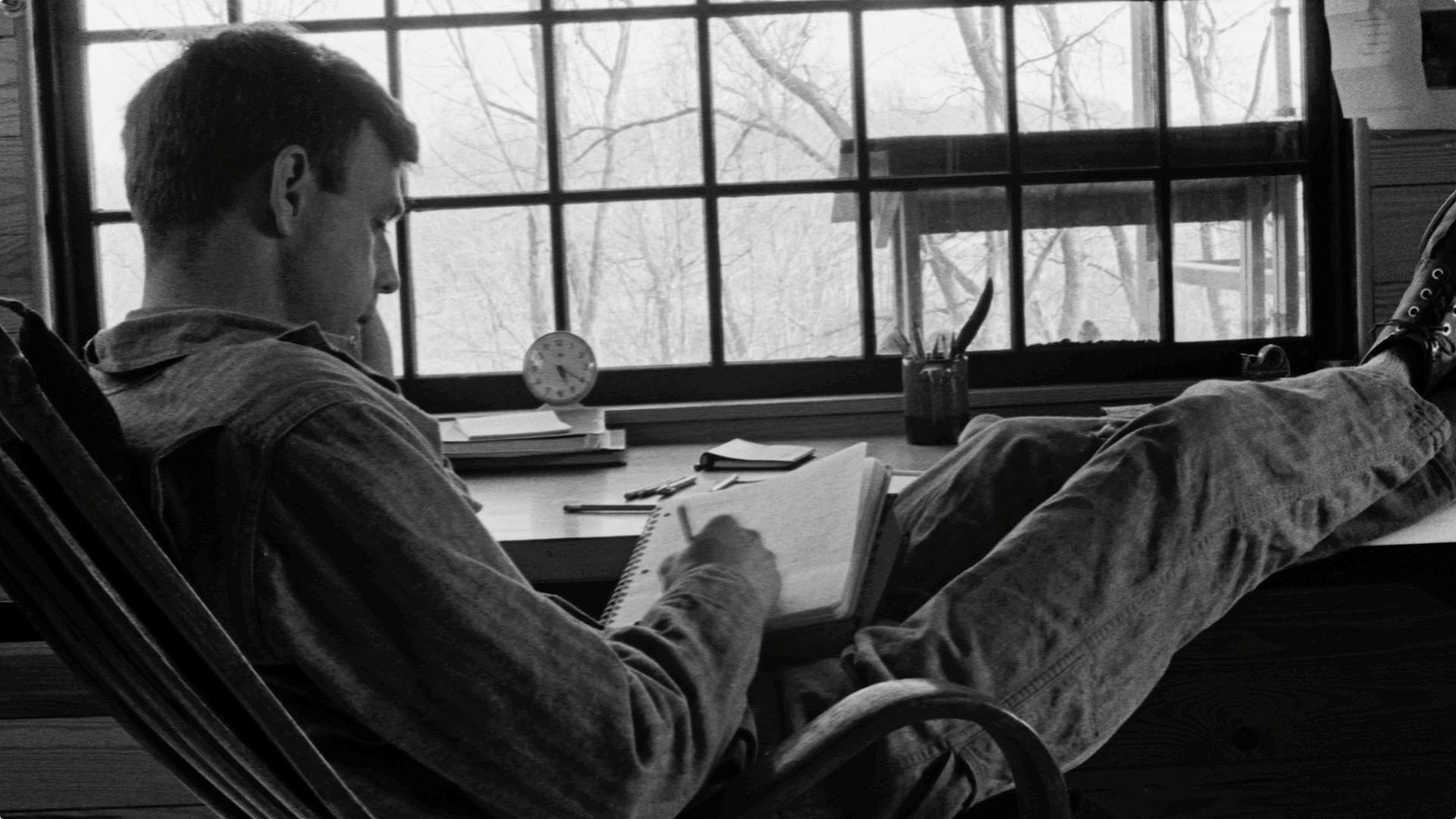

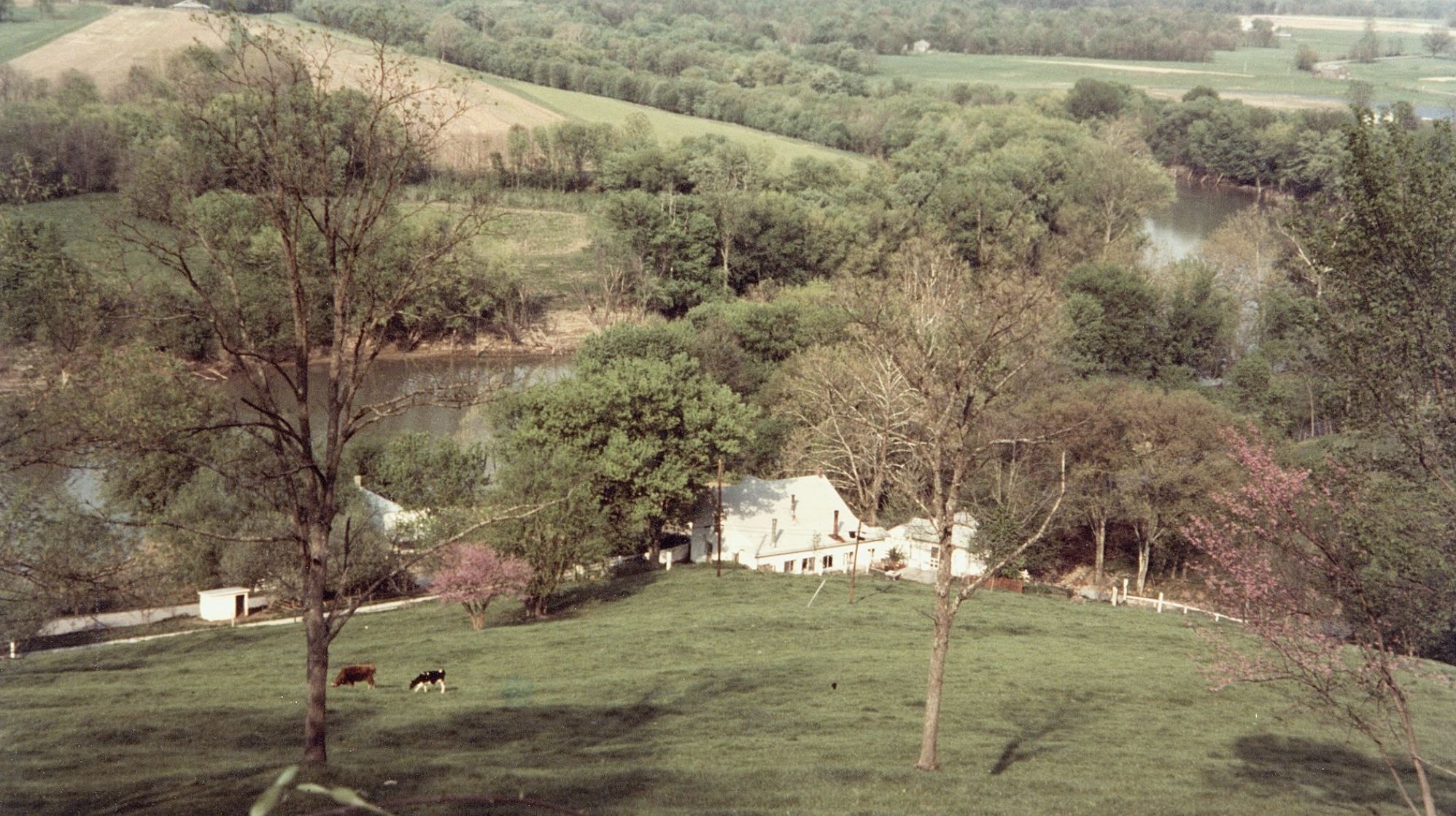

Last night, Kristyn and I finished Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry. For a while now, I’ve admired Berry from afar, as it were—not having interacted with much of his work directly save for a few essays here and there. This documentary proved why so many esteem him so highly. It also stoked in me a greater desire to read more of his work.

Toward the end of the film, Berry delivers these words as the movie splits between shots of him speaking and shots of farmers and the land:

A culture is not a collection of relics or ornaments, but a practical necessity, and its destruction invokes calamity. A healthy culture is a communal order of memory, insight, value, and aspiration. It would reveal the human necessities and the human limits. It would clarify our inescapable bonds to the earth and to each other. It would assure that the necessary restraints be observed, that the necessary work be done, and that it be done well. A healthy farm culture can only be based upon familiarity. It can only grow among the people soundly established upon the land. It would nourish and protect the human intelligence of the land that no amount of technology can satisfactorily replace. The growth of such a culture was once a strong possibility in the farm communities of this country. We now have only the sad remnants of that possibility, as we now have only the sad remnants of those communities. If we allow another generation to pass without doing what is necessary to enhance and embolden that possibility, we will lose it altogether. And then we will not only invoke calamity, we will deserve it.

To mark the beginning of Providence’s new sermon series on the seven letters to the seven churches in Revelation 2-3: Albrecht Dürer’s rendering of Christ in Rev 1:12-20

Finished reading: Becoming a True Spiritual Community by Larry Crabb 📚

A compelling account of what makes a community genuinely spiritual. Crabb writes like a modern mystic, with passion and emotional intensity. Because the reality he’s trying to describe is so ineffable, his language sounds a little odd at points. Even so, his vision is one worth pursuing.

Alastair Roberts, explaining why he traded in his obsessive reading of a certain brand of political theology for deep immersion in the gospels:

I determined to go completely cold turkey on the political theology. I stopped reading it. I stopped thinking about it. I stopped arguing about it. In its place, I steeped myself in the Gospels, reading and meditating upon them. And I prayed. […]

It was not long until I experienced a significant change; the appeal of the political theology largely dissipated. While I could make seemingly scriptural arguments for it, so much of the spirit of the politics I had been getting into was alien to the spirit of the Gospels. Reading the Gospels deeply and out of delight in them, rather than as fodder for political argument, was like leaving a thick miasma and breathing fresh air.

Part of the shift I experienced was a shift in my posture towards scripture, which led to changes in my hearing of scripture. When I was chiefly animated by political positions and debates, my approach to scripture became increasingly subservient to those. I had been “listening for” things that seemed to back up my positions. I knew all the prooftexts. I could defend my position “from” scripture too: I knew how to counter all sorts of biblical arguments against my position. […]

When I stepped back, the arguments, debates, and ideology no longer mediated my relationship with the text. I started to read it on its own terms; I started listening to it, rather than listening for things that served interests and concerns I was bringing to it. As I did, I began to feel the grain of the text and to learn to move with it. Biblical statements ceased to be brute facts to be marshalled into an extrabiblical system.

Among other things, I started paying more attention to the manner of the text and its unifying movements of thought. While I could incorporate abstract biblical verses into my former political system, I discovered that it was more difficult to honestly account for the ways the Bible itself held everything together – what it prioritized, what it said, how it said it, what it didn’t say, what it downplayed. Had the biblical authors truly believed what I had believed, they would have written very different books, with a very different animating spirit to them. And while many of my former beliefs weren’t straightforwardly wrong (although some certainly were), the spirit that animated them was, producing distortions that twisted everything.

The second to last sentence deserves serious reflection: “Had the biblical authors truly believed what I had believed, they would have written very different books, with a very different animating spirit to them.” We could change it into the form of a question, which would be a very searching question indeed: Do my beliefs about X (ostensibly drawn from Scripture) actually breathe the same air as Holy Scripture? Or we could ask: Would Paul and James and John and Peter (et al.) see the fit between their writings and the beliefs I’m espousing? Obviously, describing the “animating spirit” of a text can be a tricky business, and it’s not always a straightforward endeavor to say whether this or that biblical writer might endorse my beliefs about X. Nevertheless, I do think these sorts of questions can be useful for the person honestly trying to read with the grain of Scripture.