Currently reading: 100 Poems to Break Your Heart by Edward Hirsch 📚

Currently reading: 100 Poems to Break Your Heart by Edward Hirsch 📚

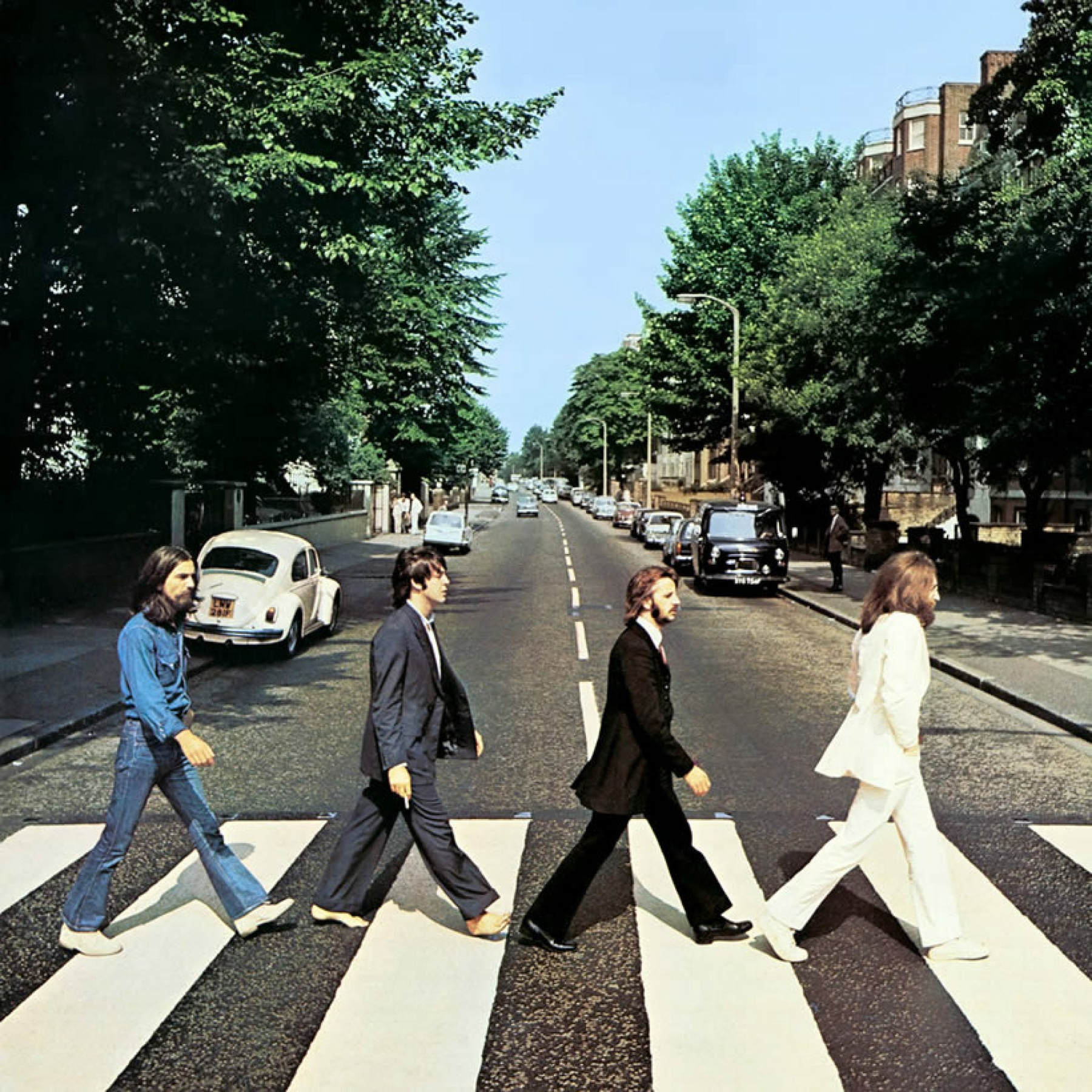

currently listening: Abbey Road by the Beatles

For me there is one spiritual mass I must fly over daily in order to catch the Spirit: morning prayer. My morning prayer isn’t long. It takes about fifteen minutes. But it is a sacrament of my sanctification. I set aside a quarter of an hour at the beginning of each day in order to set the whole day apart for the Lord. In turn, the Spirit sets me apart for the work of the ministry and sets me on the right path for a day full of direction and power. […]

Morning prayer is a fusion: prayer led by Bible reading, and Bible reading led by prayer. We pray the Scriptures, they pray in us and through us. The Scriptures inspire petition, confession, “groans too deep for words,” personal reflection, praise, joy and deep confidence to face the rest of the day. […]

Neglect of morning prayer isn’t caused by distractions. Distractibility is a symptom of a deep infection. The infection in me is my desire not to be set apart for ministry, not to be directed by the Spirit, not to be empowered to do ministry. It is, most specifically, my desire to swerve from the Way of the Cross, to set myself apart, to set my own agenda and to gather power from other sources. My refusal to do morning prayer is the Old Adam inside me, kicking against the sanctifying work of the Word and the Spirit.

Jesus specifically directed us to follow him in his life’s general direction, the Way of the Cross. Lest we object to bearing the cross as pietistic nonsense in a world of “scientific” management principles and psychological method, simply observe that virtually all the trouble that the best, most talented pastors get into comes from not following the Way of the Cross. The best and the most talented in the pastoral ministry and in denominational hierarchies harm themselves and harm the church most through their unrestrained ego and unwillingness to step off the high places. Sexual sin gets the press, but ego sin kills the church. […]

The power to do pastoral ministry and its central focus, that which gives every aspect of it meaning, lies specifically in the everyday, concrete following of Jesus, led by him on the Way of the Cross. That is how we become parables of Jesus and deliver him to the people we meet. […]

Here’s what the pastoral ministry is for me: Every day, as I go about my tasks as a pastor, I am a follower of Jesus. I am therefore a parable of him to those I encounter. The parable of Jesus works the power and presence of Jesus in their lives.

Pastoral ministry is a life, not a technology. How-to books treat pastoral ministry like a technology. That’s fine on one level—pastoral ministry does require certain skills, and I need all the advice I can get. But my life as a pastor is far more than the sum of the tasks I carry out. It is a call from God that involves my whole life. The stories I read helped me to understand my life comprehensively. My life, too, is a story, and it is the narrative quality of my life that makes my ministry happen. Others see and participate in the story as it is told. I have discovered that when I follow Jesus in my everyday life as a pastor, people meet Jesus through my life.

Currently reading: Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson 📚

Ross Byrd’s five signs of a true leader:

- Articulate Purpose

- Assume Responsibility

- Provide A Plausibility Structure

- Balance Focus with Flexibility

- Prove Yourself Trustworthy

He lands the plane beautifully with these closing paragraphs:

The hardest leadership lesson in the world is this: trust is fragile. There is only one thing that can keep the flickering flame alight, and it is not sexy. You must stay true, no matter what. As mundane as it may sound, this has become the central goal of my life.

It is a cliche in stories and films to depict kings and generals on the frontlines, leading their people into battle. But in real life nowadays, it’s almost unheard of. Just as modern warfare reassigned generals to rooms with radios and radars, far from the blood and mud of the battlefield, so too modern wisdom has reassigned leaders to places and spaces far removed from the day-to-day labors of their people. “Relentless delegation” is the wave of the future. There are more business books written today about how to “work oneself out of a job” than there are about how to lead others within one. I have no major qualms with delegation, especially if you’ve already cut the path for others to walk. However, the increasing removal of founders, owners and officers from the daily lives and work of their organizations’ members does seem to underestimate the primary source of human motivation.

What moves people, really? Why do people persist in doing hard things? Why venture into the wilderness? Why rush into battle? Despite what a million “mission and vision” statements may proclaim, people follow people, not principles. When we delegate, when we scale, we invite new benefits, of course. But we also open ourselves up to new forms of fragility. It doesn’t mean a leader shouldn’t grow his organization, anymore than a father and mother shouldn’t grow their family. Growth is a blessing. And yet, at every level of growth, the question must still be asked: Not, “What are they working for?” but “Who are they working for? Do they have someone to follow who will not let them down?” For my money, this is what makes or breaks our companies, communities, ministries and families. We are not Christ, but if we hope to be good leaders, we must be like him in this way most of all. We must become trustworthy.

photo cred (and staging) goes to: Bella

Currently reading: The Art of Pastoring by David Hansen 📚

I’m picking out a few gems from Abigail Favale’s “Rethinking Complementarity":