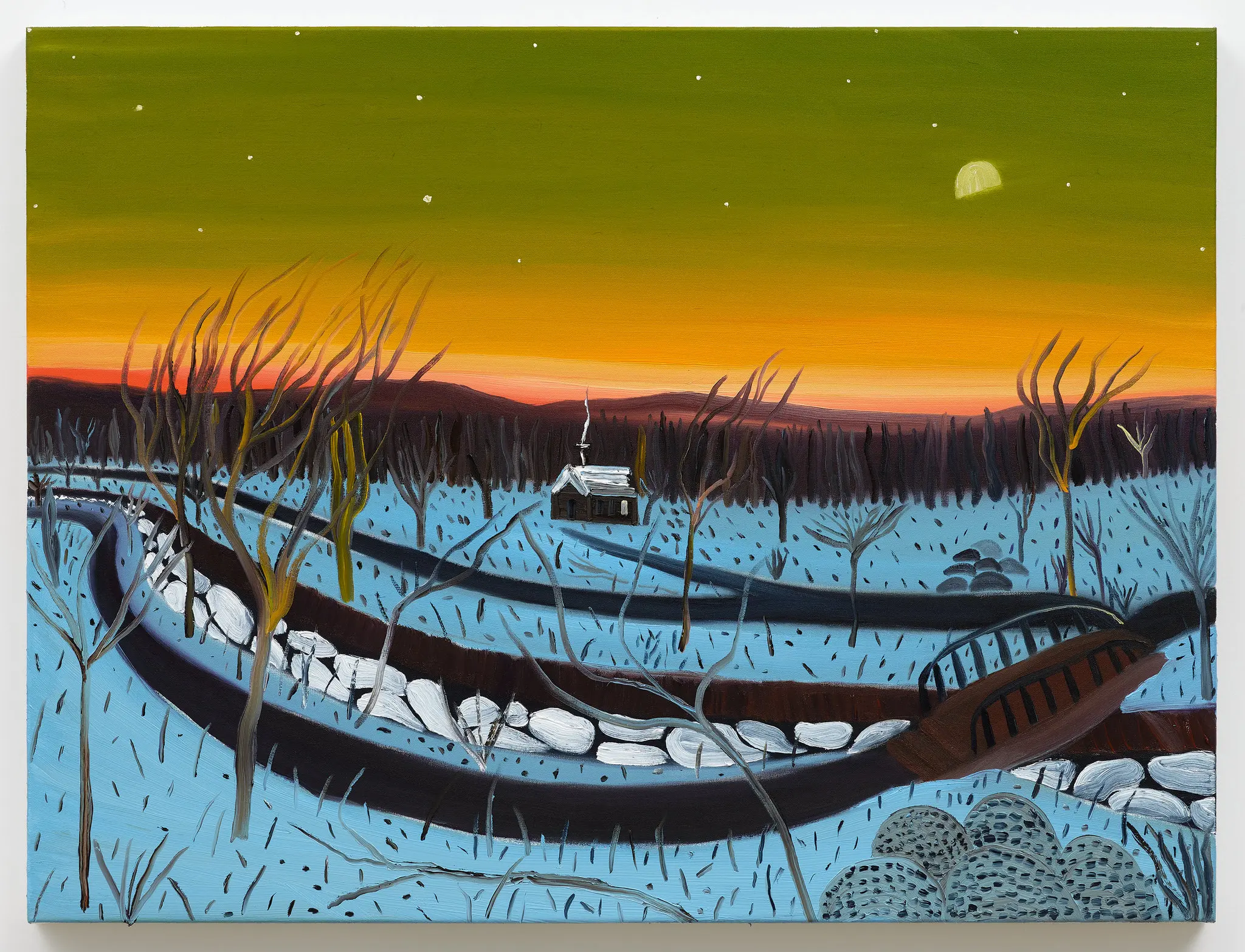

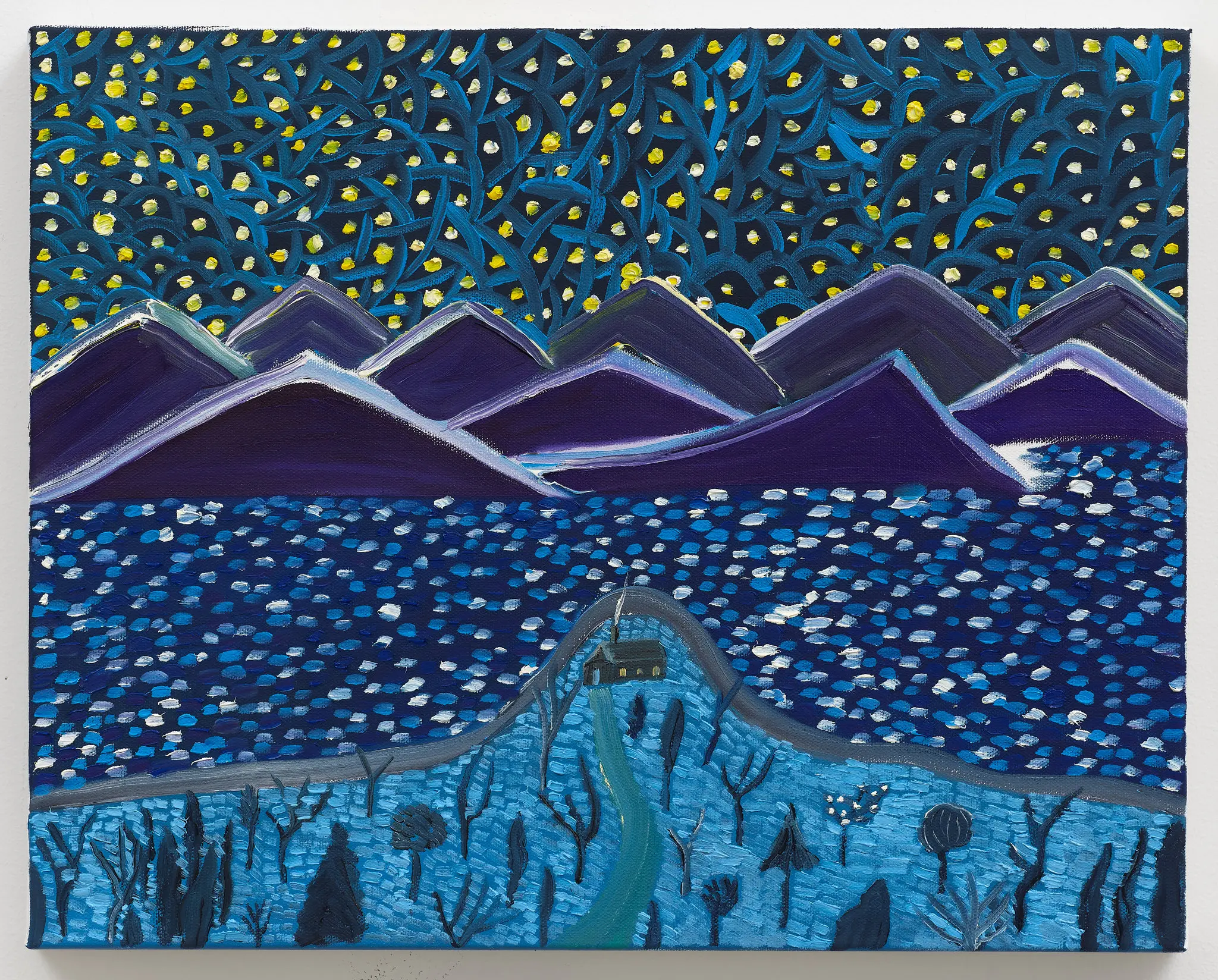

The Kingdom by Matthew Wong:

The Kingdom by Matthew Wong:

From the 2019 New York Times obituary for Matthew Wong:

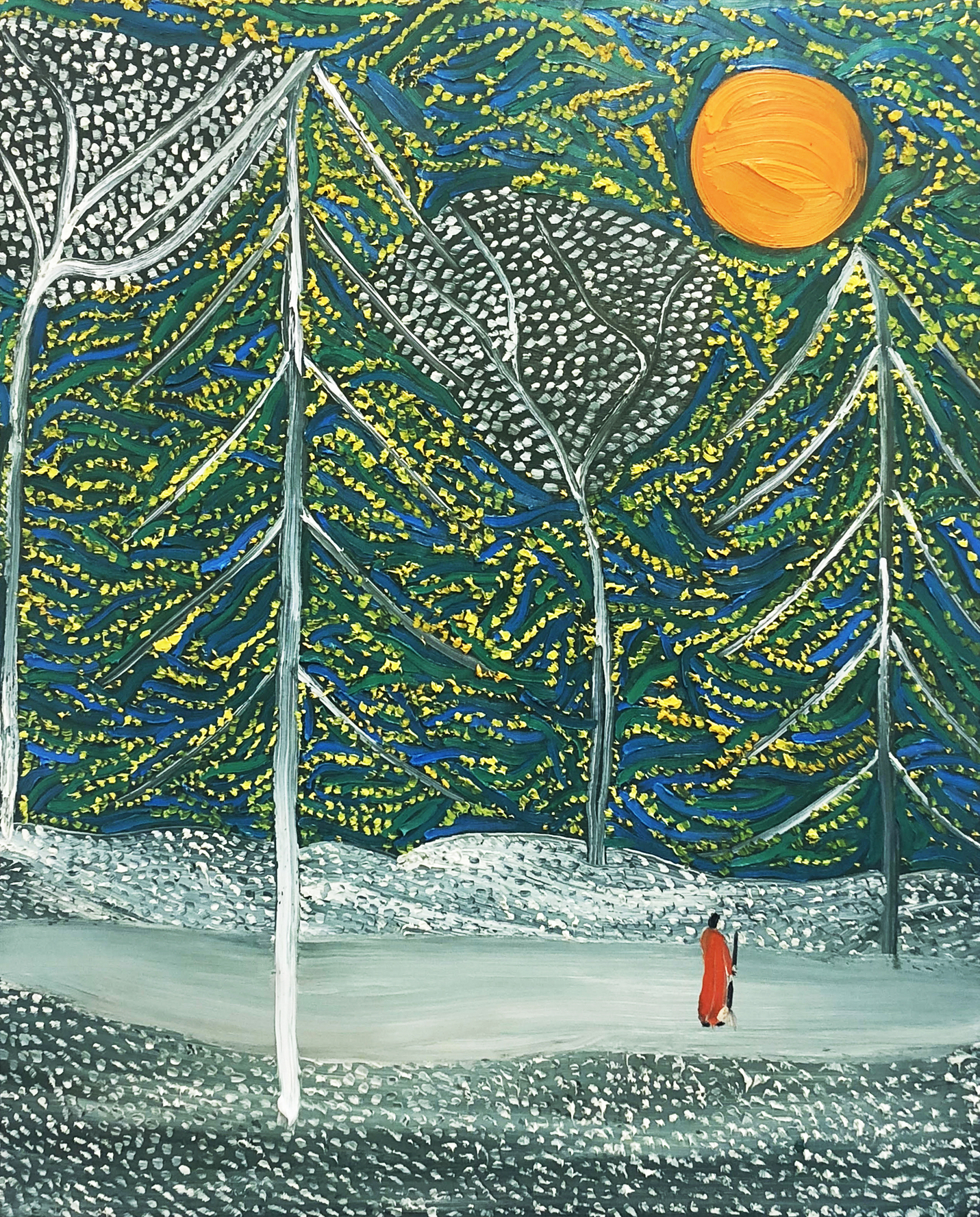

From a 2018 interview with Matthew Wong, in response to a question about the “hints of melancholy” in his work: “I do believe that there is an inherent loneliness or melancholy to much of contemporary life, and on a broader level I feel my work speaks to this quality in addition to being a reflection of my thoughts, fascinations and impulses.”

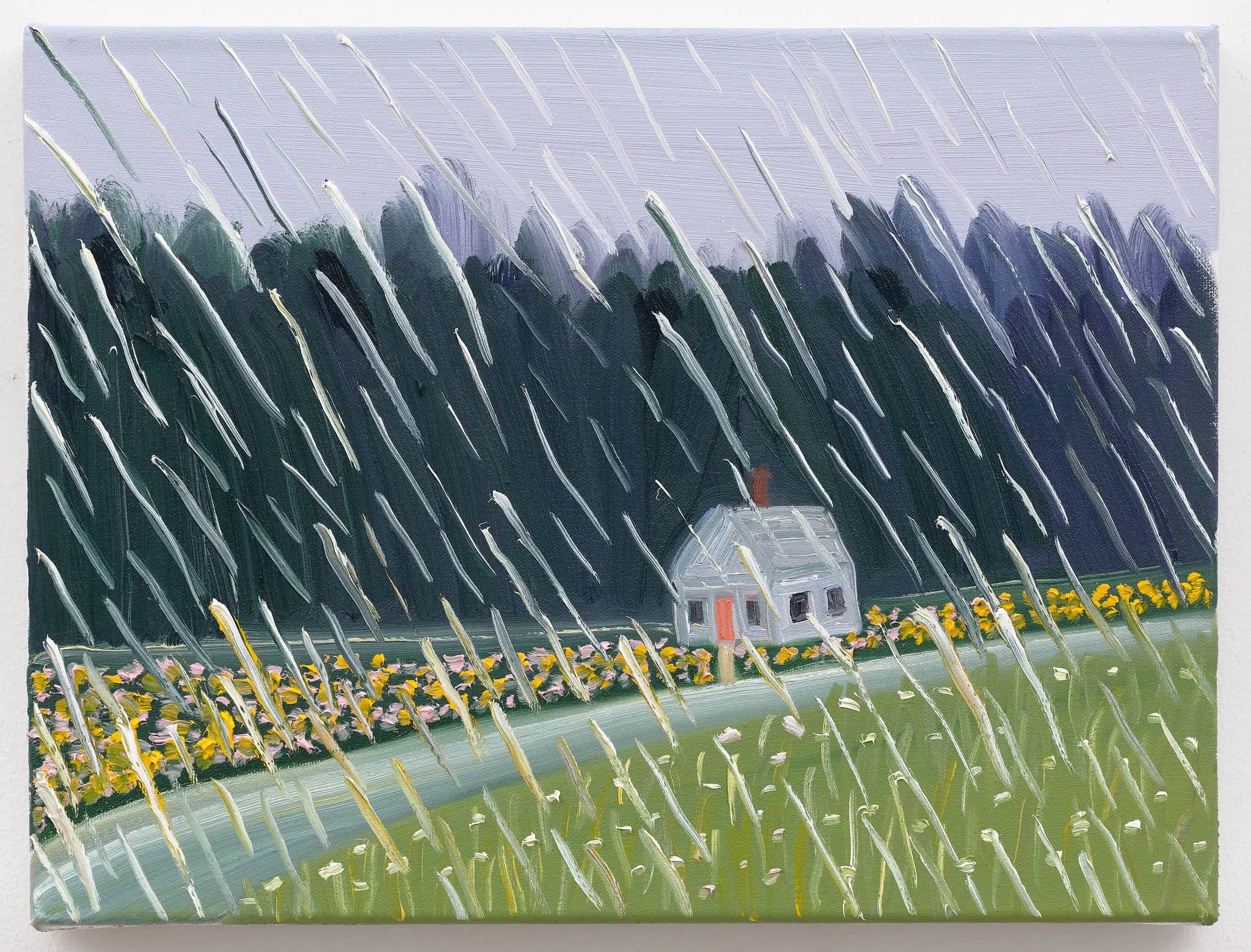

Coming of Age Landscape (2018) by Matthew Wong:

The first virtue of all exercises of authority in this life is mercy. Following Christ, who (quoting Hosea) urged us to “Go and learn what this means: ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice’” (Matt. 9:13), mercy is a crucial part of the vocation of political authority in this world. Yet this is not because of fear on the authorities' part of “blowback” from God—not, that is, because of fear of one’s own judgment by God—but because this is the central truth about God’s judgment of the world. God is merciful, first and foremost. Therefore, if authorities want their action to conform to the “author” of that authority, the actions of that authority must manifest mercy as well. This is a persistent theme in Augustine’s writings: again and again, in his treaties, in his sermons, and above all in his letters to political authorities, he underscores the need to recognize the preeminence of mercy in judging.

Why are we so committed to the idea that we are all unique and fundamentally free individuals? (Indeed, this collective belief in our discrete individuality is one of the things that makes us moderns so alike.) What is the source, and the rationale, of this belief in individuality? This dogmatic bias against authority is rooted in beliefs we have about the nature of the human as an agent. These rely on anthropological convictions, convictions about the picture of the human agent we assume. To dislodge them, we have to tackle their philosophical fundaments directly.

The forces encouraging and reinforcing this picture of the human are complex and manifold. On the surface, the problem may seem to be linguistic. Our language of “choice” offers no way to acknowledge our participation in, or vulnerability to, one another; it assumes that we are fundamentally separate from one another…. It seems incoherent, or at least improper, to attempt to wrest another’s choice out of another’s control; given the basis of such choice in the mysterious subjectivity of the agent (“there’s no arguing with taste,” as the saying goes), it seems almost a category confusion to imagine that one could exercise another’s choice for him or her. […]

But note here how we are already moving from problems in our language to some more fundamental philosophical presuppositions underlying that language, presuppositions about the human agent. A large part of our problem here—I do not say the whole problem, merely a large part of it—lies in the picture of human agency most of us unreflectively assume today, and in this picture’s depiction of the relationship between God, humans, and creation. This picture…assumes that human agency properly operates through radically unconstrained choice, which is modeled on the radically unconstrained, ex nihilo action of God in creation. It is, in short, a Promethean vision of the human—a vision that emphasizes the human’s capacity to act while ignoring or downplaying the constraints on the human’s dependency on forces and persons beyond the human. To be sure, it relies on and obeys real authorities…but it cannot explicitly acknowledge them as authorities. This ex nihilo picture cannot, that is, understand authority. It offers no way to acknowledge our enmeshment or participation in, or vulnerability to, one another; it assumes that we are fundamentally separate from one another. Here love appears as nothing but the negotiation of our individual, private happiness. See in this light, our perplexities about civic engagement are rooted in deeper philosophical perplexity about our self-understanding as agents, and indeed as humans: we talk, that is, as if we do not believe that love is the core of our being; as if we believe that the world is ultimately a matter of sheer power, of conflicting wills, without respite; as if we want to be left wholly alone. Beneath our latent Promethean idolatry is a deep existential despair, a sense of being alone, of being abandoned.

Andy Crouch’s definition of human persons would go some way toward remedying this deficiency: “Every human person is a heart-soul-mind-strength complex designed for love.” Imagine the political ramifications of taking that definition seriously. Crouch expounds,

We are designed for love—primed before we were born to seek out others, wired neurologically to respond with empathy and recognition, coming most alive when we are in relationships of mutual dependence and trust. Love calls out the best in us—it awakens our hearts, it stirs up the depths of our souls, it focuses our minds, it arouses our bodies to action and passion. It also calls out what is most human in us. Of all the creatures on earth, we are by far the most dependent, the most relational, the most social, and the most capable of care. When we love, we are most fully and distinctively ourselves.

Authority seems invisible to us because it is so pervasive in our world. In fact, pretty much the entire discipline of sociology is built on this puzzle. How is it, sociologists ask, that human society, which is so profoundly complex, essentially involving the voluntary consent and synchronization of so many millions, and now billions, of people—how is it that society works so smoothly? (Sociologists spend a good bit of their time studying deviance, but that’s really an avoidance mechanism for them; the real mystery at the heart of sociology is not that there are some people who break the rules, but that there are so very many who do not.) Clearly, society works as well as it does because people obey. They order their lives according to some fairly sophisticated, if rarely articulated, rules. […]

Humanity today, for all our talk about individuality, is a remarkably docile, obedient, and rule-bound species. Authority is all the more powerful for being so thoroughly imperceptible. Its ultimate triumph lies in how it is embedded in our psyches: we obey authority when we think we ought to do something. The sociological discussion of authority begins from the fact of the pervasiveness of obedience and conformity.

Charles Mathewes, trying to gesture at a more robust anthropology than the one undergirding consumer capitalism, which assumes that “individual choice” is the fundamental category of agency:

For Augustine, the fullest picture of good human agency is human agency as it will be exercised in the eschaton. He characterized that agency in a famous Latin phrase, non posse peccare, when humans will find it “not possible to sin.” For him, true, fully achieved human agency was not one where “choice” played any role at all, but rather was a kind of full voluntary exercise of one’s being, where one is wholly and willingly engaged—but where one seems to have no choice about this. This does not require compulsion of any dangerous sort; after all, it is “involuntary” in much the same way that one has no choice about laughing at a funny movie, but one laughs, at times (if it is really funny) with more than one’s voice—with one’s whole being. For this to happen we must be liberated from the slavery to sin to which we are all manifestly, for Augustine, captive. It is that enslavement that divides or splits our will and so sunders our integrity. Here is a picture of idealized agency where the center of the picture is not a wide range of options, but no options at all—a picture of human agency whose flourishing lies wholly in the complete and unimpeded engagement of the whole person in the dynamic joy of paradise.

This is an entirely different picture of agency, one that highlights humans' capacities of participation, receptivity, and particularly love: aspects of agency that subvert a picture of the human as fundamentally active. Love is the “root” of the soul, and so we are in a way composed by our cares: we do not make things valuable, the things that we value “make” us—or better, reveal who we truly are. When the soul is properly oriented in the love that is caritas, it is a unifying force, equally for our own self-integrity, our relationship with God, and our relationship with our neighbor. But love is not only an affective orientation toward things we care about, it is also intelligent, an articulate cognition of our situation, an attempt at assessing the true value of the world and the things within it. So when Augustine (in)famously says “love and do what you will,” he does not mean do what you will, insofar as the you is the you that you were before you felt God’s love; rather, that love has so transformed you that you now will to do love.

On this picture, joy is what we receive, a gift. We do not pursue it; we are always surprised by it. And what we do is bear it to others; it is by nature communicative. In loving, you become an instrument of God, and a vehicle for God’s love of the world. Hence caritas is politically unifying: as this energy has been directed toward the conversion of the self back to God, so it in turn energizes the self to seek communion with others. This is not a form of violence; we love others in friendship and treat them as would God.

This understanding of freedom entails a particular picture of the nature of human agency, one that sees such agency, at its core, as a matter of response to God’s action upon it, not as a matter of simply self-starting willy-nilly into the world. Furthermore, it is fundamentally responsive to a longing that is primordial to its being, the longing for God, so that all our acts are to be understood as forms of seeking our true home in God, a seeking that is also a beseeching, a pleading to God to come to us. As such it is both active and passive, with the passivity taking the lead. The primordial act of our agency, that is, is to respond to the eliciting call of God—to listen, or hear, or attend, or—most properly—wait on God. In doing this, we should see ourselves not as desiring but as desired, as objects of love before we are agents of love. Our destiny is not primarily to do something, but first and foremost to be loved.

Today our capacity to be creatures who love—who have long-standing and deep attachments that are irreducible to sheer animalistic appetites—is threatened, left to atrophy, by the consumerist mode of life we inhabit.

What does it mean to say that our mode of life challenges our capacity to love? It means that we are increasingly encouraged to think about desire and longing in ways detrimental to long-term commitments. Consider: I can get anything I want. But do I know what I actually “want” at all? Our world is awash in accessible consumer goods and pluriform forms of life, but this flood of consumables has seemed to go hand in hand with a growing sense of skepticism and even indifference to any good in particular. At the same moment when the good life, in multiple flavors, is being offered to us, we seem increasingly incapable of wanting any particular form of it for more than an instant. We live in an economic culture of immediacy and consumption, in which the idea of patience or waiting has no home to rest its head. Consumer culture “takes the waiting out of wanting,” encouraging us toward a kind of constant appetitive channel surfing, as one fickle appetite follows quickly upon another. This condition does not so much directly reshape us as indirectly mislead us: for it tells us, or sells us, a story about ourselves, and through that story seduces us into believing the illusory promise of immediate satisfaction. This promise is a powerful one; if we come to believe in it, we come to see ourselves as being the kinds of creatures who have only the sorts of short-term desires that consumer culture can satiate.

That last line is haunting. Already, we seem to be far down the road of desiring little beyond our short-term, animalistic appetites. I’m reminded of Lewis' famous line: “If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world.” Of course, I still believe that those desires are deep within each person, but they are getting smothered. Such desires lack the time and quiet and patience to bubble up; they’re shouted down by lesser desires before they find the space to come to expression.

Charles Mathewes, speaking here on the delicate topic of “understanding” the evil perpetrated by terrorists, but with much broader application:

Consider a simple question. What does it mean to seek to “understand” evil? Initially I suspect the decent mind recoils from such an undertaking. If “understanding evil” means to render it intelligible in the sense of excusable or even rational, then such “understanding” is, I would argue, intellectually delusionary, psychologically futile, and morally hazardous. But this question can be taken in another, deeper, sense: here understanding is simply the project of depicting evil as something within the realm of human behavior, as something that we could conceivably do.

It is probably impossible not to feel the tug of the first form of understanding. Yet we should resist it as strongly as we can. That we could be like these “others” in different circumstances does not mean that we are in fact relevantly similar to them, and hence lacking any standing to judge them. Judging requires both sufficient proximity to secure a good sense of the matter at hand and sufficient distance to ensure that one is not improperly confusing one’s own interests and concerns with the situation.

The question is important because we need to know “the enemy” precisely in their enmity to us—their rationale for why they do what they do. To do this we must resist the all-too-human reflex to alienate them as “the enemy,” to see them as fundamentally different from us, fundamentally nonhuman. (This is not to deny others' sole responsibility for their particular acts of malice; it simply identifies the disquieting fact that this behavior is, in some way, done by creatures inescapably, disquietingly like us.) Yet we must also resist the counterreflex to depict (and tacitly excuse) them as “just misunderstood.” Instead we have to see them as continuous enough with us to be recognizably human, but take no comfort in the fact of their bare “humanity” as somehow securing them from the possibility of being, paradoxically, monstrous.