Our makeshift table in the living room for dinner/games with family this evening. It passed Lewis’s inspection.

Our makeshift table in the living room for dinner/games with family this evening. It passed Lewis’s inspection.

An interesting piece from Jake Meador at Mere O on the reigning paradigms of cultural engagement within American evangelicalism: 1) the “faithful presence” approach—embodied by Tim Keller—in which Christians don’t seek (or, at least, don’t presume) control of elite, public institutions but do attempt some level of presence and influence; and 2) the “owned space” approach—Doug Wilson being the exemplar—in which Christians seek out spaces where they can have controlling influence. Meador summarizes, “This, then, is the divide that now exists within politically engaged evangelical Christianity in America. One group is trying to create ecosystems of Christian presence within pluralistic contexts while the other is seeking to build bulwarks of owned space.”

He goes on in the piece to acknowledge the strengths and shortcomings of each approach. Given his deep admiration for Keller, it’s commendable that he speaks forthrightly about how faithful presence can easily drift toward accommodation and compromise—in other words, toward unfaithfulness. Ultimately, though each approach has problems and potential pitfalls, Meador argues that the “faithful presence” approach is the best (and I would concur).

I would, however, quibble with Jake’s characterization of this divide between the two groups as “being a dispute between varieties of Hunterians.” I’ve noted before how Hunter’s work has been regularly misappropriated. To call the “owned space” view a “variety of Hunterianism” is, in my view, to perpetuate this misreading. To be clear: I’m not even commenting on the merits of the “owned space” view; I’m simply making the point that it shouldn’t be considered a species of “Hunterianism.” Wilson’s program of cultural engagement had been up and running for decades by the time To Change the World was published in 2010. The fact that Wilson happened to agree with Hunter that evangelicals possess a superificial (read: wrong) view of culture and how it changes does not mean that their projects ought to be lumped together.

Upon reflection, I think the reason why Hunter’s work has been so consistently misread is that To Change the World is part descriptive sociological analysis and part prescriptive scriptural reflection. But the term “faithful presence” flies as a banner over the whole thing. So, if you agree with Hunter’s sociological analysis (and, frankly, who wouldn’t?), then it doesn’t matter what you believe should be done in response. You might completely reject Hunter’s proposal in the last section of the book. Indeed, many people seem to derive all sorts of oughts for what Christians should do (infiltrate elite institutions, prioritize the arts, etc.) from the is of Hunter’s analysis (cultural change happens through tightly connected groups of elites operating at the centers of cultural power). Ironically (and Hunter is attuned to irony), his analysis ends up getting deployed in service of the same Nietzschean pursuits that he attempts to unmask in Part Two of the book.

So, my counsel: Let’s all agree that one is only a genuine Hunterian, a true purveyor of “faithful presence,” if one agrees (at least in large measure) with Hunter’s proposals in the final part of To Change the World. Faithful presence involves not merely agreeing about the mechanics of cultural change, but agreeing that attempts to sit in the cultural driver’s seat are wrong-headed from the start. To be faithfully present is not to strategically target elite institutions, but to embed ourselves in the vast multiplicity of spaces and environments that Christians have been scattered—whether culturally significant or forgotten, influential or despised.

I’m currently listening to The Second Mountain by David Brooks on my commute (not reading it, mind you; don’t @ me). So far I’ve really enjoyed it.

One arresting anecdote I heard on the drive home this evening (which I was also able to locate in this 2019 piece): In describing those experiences that hint at a reality beyond our ordinary existence, Brooks tells the story of a friend who, when her first daughter was born, “realized she loved her more than evolution required.”

I’ll be pondering that line for a while.

Brad East, in the course of encouraging pastors to read fiction and poetry, describes how such reading is, in fact, a species of leisure—of Sabbath:

In a word, reading partakes of the Sabbath because reading is non-utilitarian. Like poetry, in Auden’s line, it “makes nothing happen.” It is the opposite of activism. It is a mortal threat to the anxious soul of the busybody, the savior of his parish, the CEO of his congregation, the leader without whom the world would fall to pieces.

It won’t. The world will keep spinning long after you’re dead, and it will keep spinning now, while you sit in your study and make your way through Dante. In fact, both your faith and your church will benefit far more from your having journeyed through hell and up the mountain into paradise than from your having responded to every email in your inbox. (In writing this, you understand I am chiefly addressing myself.)

The closer one’s reading habits are to the utilitarian—mining for sermon illustrations, shoring up biblical backgrounds, cribbing ideas for self-help—the further they are from the Sabbath. Pastors should already be in the ninety-ninth percentile of readers, setting aside multiple hours per day. That goes without saying: it’s right there in the job description. The question is what their diet should consist of. Francis is right that it should include fiction and poetry, the uselessness of which is precisely the uselessness of the seventh day.

A hearty Amen to the whole piece. Surely, though, Brad knows that pastors are not in the ninety-ninth percentile of readers and are not setting aside multiple hours a day for reading. Anecdotally, the pastors I’ve encountered did their reading in seminary and, once settled in a church, read perhaps a few hours a week, mostly commentaries on the text to be preached or online articles. Forget fiction or poetry; most pastors don’t read Biblical Studies or Theology. Perhaps that needs to be remedied first before moving on to these—how should we say it?—leisurely pursuits?

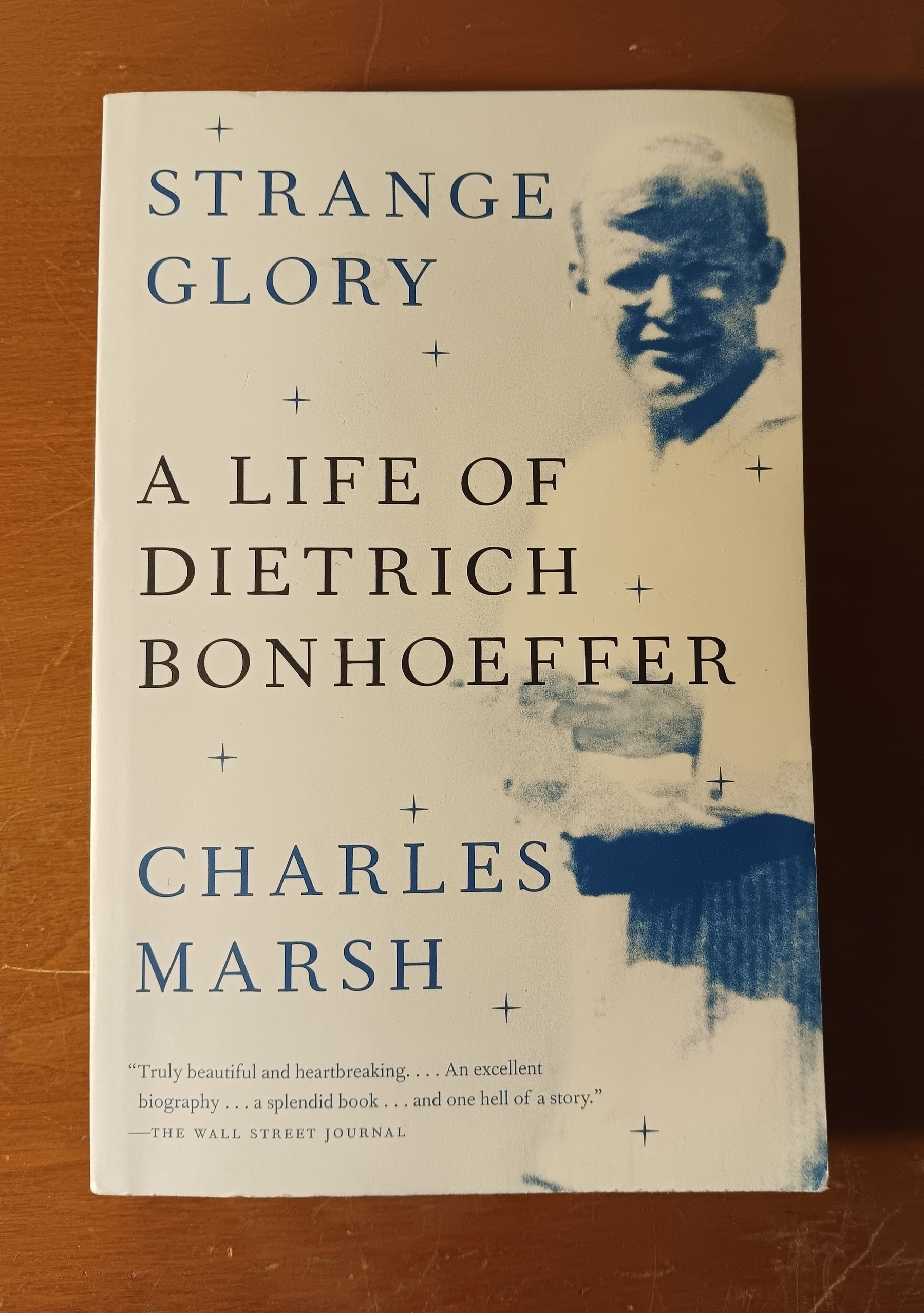

Charles Marsh, in a long essay in which he responds to criticisms of Strange Glory (particularly those leveled by Ferdinand Schlingensiepen), with some ruminations (selectively chosen on my part) on biography as a genre and his approach to his subject, Dietrich Bonhoeffer:

The biographer feasts upon the singularities of lived experience. […]

As Leon Edel writes, “Biography is a record, in words, of something that is as mercurial and as flowing, as compact of temperament and emotion, as the human spirit itself.” To which I would add that biography is memory of particular bodies committed to narrative. […]

My approach was to portray Bonhoeffer in his singular complexity, which is to say, his strange glory. […]

At the level of craft, telling a theological life should be no different than telling any other kind of life. Every good biographer maintains the desire to save a personality from the clutch of familiarity. The challenge is in determining how to enlist the tenets of belief in service to story. The infinite does not appear in the dramatis personae; instead, theologians enumerate transcendence under the terms of specific doctrinal commitments. It may be said of the theological biography that it tells a life out of a “higher satisfaction” (to borrow a phrase from Bonhoeffer), but this should not be taken as a method or dogma. The theological biographer writes with the hope of rendering the character’s faith as vivid and credible elements of the story. Otherwise I feel rather agnostic toward the idea of a theological biography. […]

Biography is built on historical reality, of course, but its purpose is finding the truth in the life. This does not mean finding the authentic or essential self but the patterns and manners, “the doubts and vulnerabilities, ambitions and private satisfactions that are hidden within the social personality.” […]

Biography came to me as a quest to capture what Hermione Lee describes as “the ‘vital spark’ of the human subject.” To readers familiar with Bonhoeffer’s story, I wanted to create a sense of discovery so that they could encounter him as if for the first time, encounter him in his strange glory. For those unfamiliar with Bonhoeffer, I wanted to do all the things biographers hope for when they write well: approximate in narrative nonfiction “the presence of recognizable, approachable life . . . to catch the special gleam of character.”

Finished reading: Strange Glory by Charles Marsh 📚

A truly great biography. Marsh succeeds brilliantly in rendering a concrete, flesh-and-blood Bonhoeffer. Marsh’s prose is lyrical, his grasp of Bonhoeffer’s thought is deep without being tedious, and his narrative pacing is expert. I expect to be haunted by Strange Glory for quite some time.

Currently reading: Uprooted by Grace Olmstead 📚

right before we loaded up for the return trip to Austin