The massive growth and influence of cities in our time confront Christian mission with an enormous challenge. The first problem is one of sheer scale and economics. It is critical that we have Christians and churches wherever there are people, but the people of the world are now moving into the great cities of the world many times faster than the church is. Christian communication and ministry must always be translated into every new language and context, but the Christian church is not responding fast enough to keep up with the rapid population growth in cities.

Finished reading: Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World by Jason Hickel 📚

This was my first foray into the “degrowth” realm. And I have to say: Less is More packs a serious punch. As one reviewer put it, “The entire book is a withering—and very persuasive—indictment of capitalism’s generally pernicious impact on, firstly, human society, and, more recently, on the natural environment on which we all ultimately depend.” Capitalism is the boogeyman in Hickel’s story. But it’s not really capitalism per se that’s at issue; rather, it’s the cultural/moral/metaphysical logic of extraction and growth undergirding our capitalist system. As Hickel explains,

What makes capitalism different from most other economic systems in history is that it’s organised around the imperative of constant expansion, or ‘growth’; ever-increasing levels of industrial extraction, production and consumption, which we have come to measure in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Growth is the prime directive of capital. Not growth for any particular purpose, mind you, but growth for its own sake. And it has a kind of totalitarian logic to it: every industry, every sector, every national economy must grow, all the time, with no identifiable end-point.

Less is More paints with a broad brush in telling the history of capitalism. Events like the Enclosure Movement and people like Descartes loom large in his telling. I’m not really interested in quibbling over the narrative because I think he arrives at the conclusion that any sane person would, regardless of what you make of the political/cultural/intellectual/economic forces feeding into it. His calls for a “Post-Capitalist World” were intriguing (e.g., end planned obsolescence, cut advertising, shift from ownership to user ship, end food waste, scale down ecologically destructive industries), though the political means of achieving such ends were rather opaque.

One of the most surprising aspects of the book: Hickel’s understanding that the shift required for “degrowth” is not merely economic or political; indeed, it is essentially spiritual or metaphysical. He speaks approvingly at several points of animistic groups who—unlike the western and dualistic Enlightenment thinkers who’ve bequeathed to us a legacy of viewing humans as distinct from the rest of the natural world—see humans as “interconnected” with the rest of nature. What’s required is not merely an imposition of limits, but, as he notes, “new theories of being.” In the last few paragraphs of the book, Hickel explains why he chose to address the problem of climate change and environmental breakdown through the lens of “degrowth”:

[Degrowth] stands for de-colonisation, of both lands and peoples and even our minds. It stands for the de-enclosure of commons, the de-commodification of public goods, and the de-intensification of work and life. It stands for the de-thingification of humans and nature, and the de-escalation of ecological crisis. Degrowth begins as a process of taking less. But in the end it opens up whole vistas of possibility. It moves us from scarcity to abundance, from extraction to regeneration, from dominion to reciprocity, and from loneliness and separation to connection with a world that’s fizzing with life.

Ultimately, what we call ‘the economy’ is our material relationship with each other and with the rest of the living world. We must ask ourselves: what do we want that relationship to be like? Do we want it to be about domination and extraction? Or do we want it to be about reciprocity and care?

This sounds an awful lot like Wendell Berry in his “Two Economies” essay (HT: Alan Jacobs):

For the thing that so troubles us about the industrial economy is exactly that it is not comprehensive enough, that, moreover, it tends to destroy what it does not comprehend, and that it is dependent upon much that it does not comprehend. In attempting to criticize such an economy, it is probably natural to pose against it an economy that does not leave anything out. And we can say without presuming too much, that the first principle of the kingdom of God is that it includes everything; in it the fall of every sparrow is a significant event. We are in it, we may say, whether we know it or not, and whether we wish to be or not. Another principle, both ecological and traditional, is that everything in the kingdom of God is joined both to it and to everything else that is in it. That is to say that the kingdom of God is orderly.

Hickel certainly sees the church as part of the problem—i.e., one of the contributors to our current “dualistic” worldview that’s led to the extractivist logic of capitalism. Berry’s comments suggest that the Christian religion does, in fact, have resources internal to it that could fund just the sort of wholesale imaginative re-envisioning of the world that Less is More is calling for. All I can say is: We shall see.

Landscape with a Woodland Pool (c. 1497) by Albrecht Dürer:

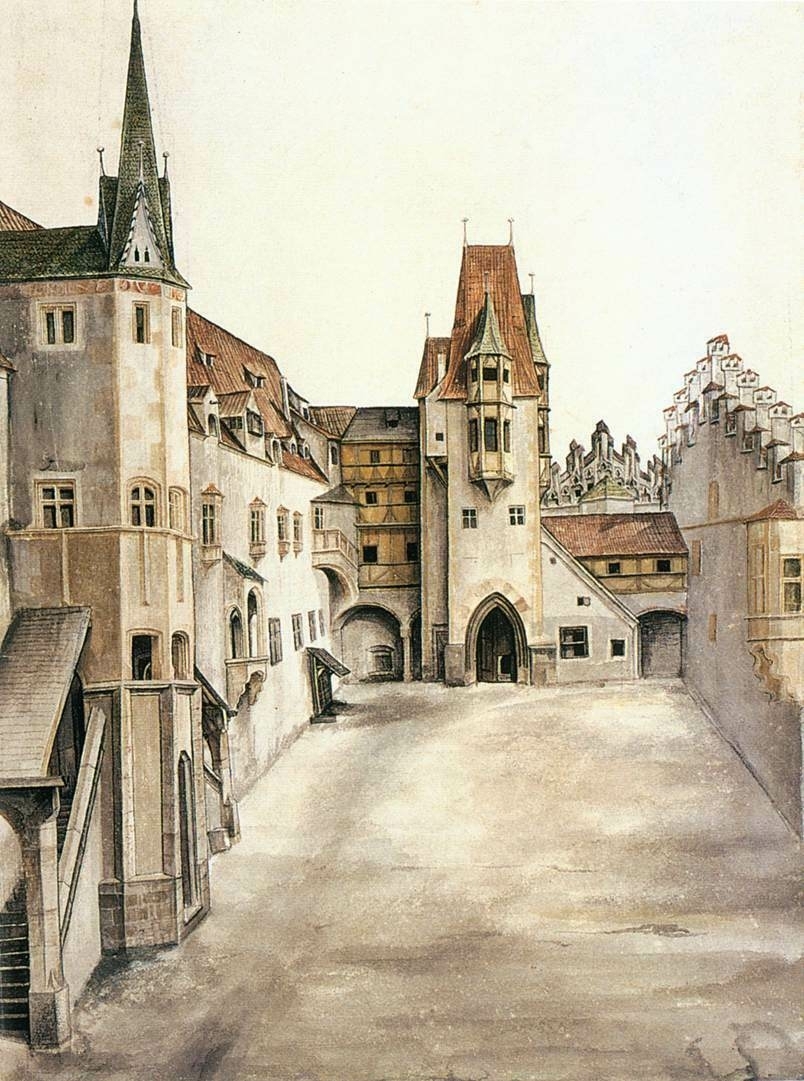

Courtyard of the Former Castle in Innsbruck without Clouds (1494) by Albrecht Dürer:

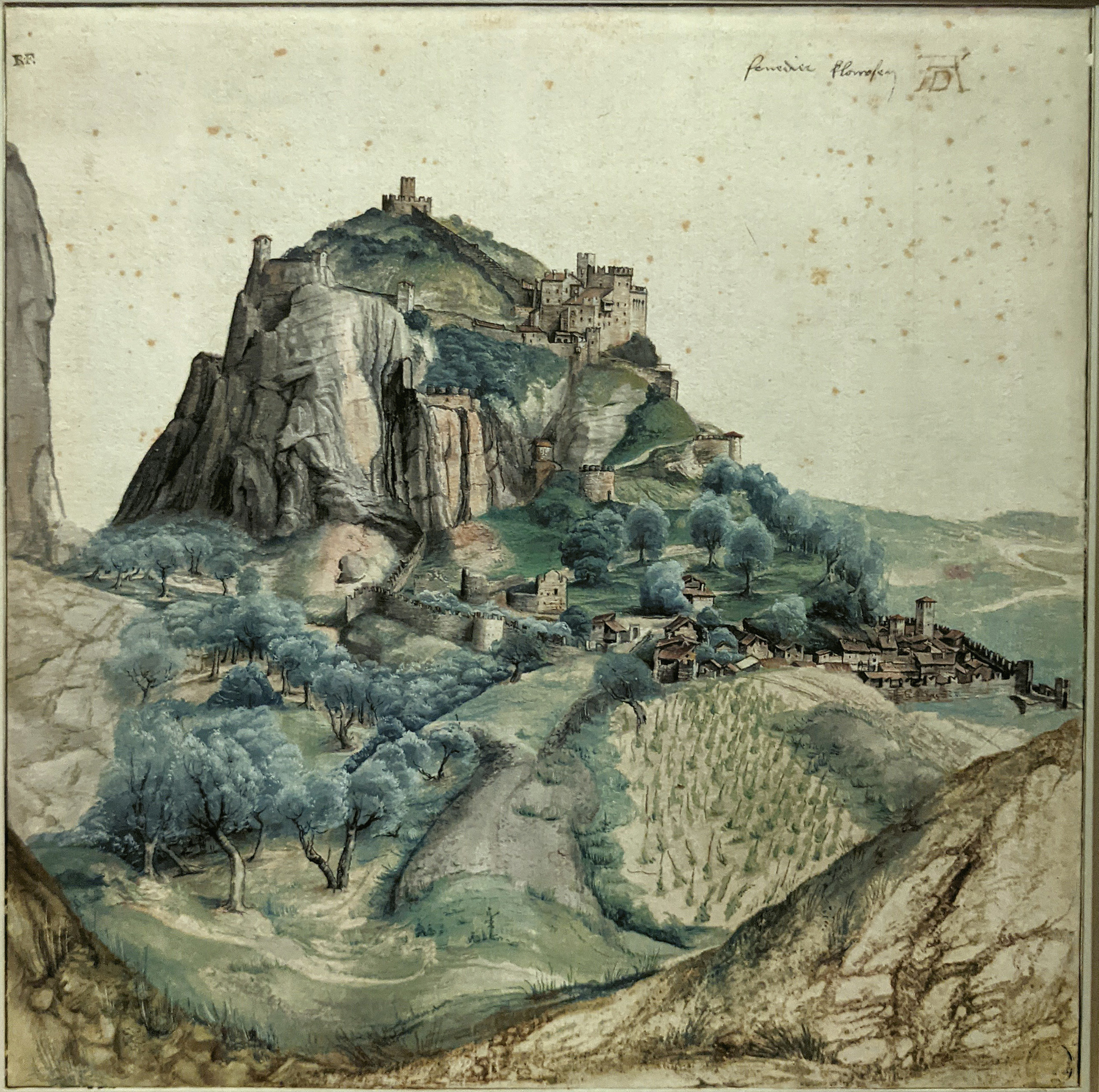

View of the Arco Valley (1495) by Albrecht Dürer:

Currently reading: The Revenge of Conscience by J. Budziszewski 📚

Philip Bess, in an old two-part essay at Public Discourse (here and here), makes the surprising argument that the proposition “human beings should make walkable mixed-use settlements” ought to be considered a hypothetical tenet of the natural law. While making appropriate qualifications (e.g., Bess does not claim that living in such settlements is morally obligatory or makes one morally superior), Bess suggests that our cultural patterns of building are not merely about subjective or aesthetic judgments; rather, they root in substantive understandings of human nature and the telos of human life. Which means that the anthropology implied by “urban sprawl” is an individualist one, enamored of choice and personal freedom and private property and home ownership. As a good Thomist, Bess believes that “walkable mixed-use settlements” better accord with our nature and allow us to more fully realize our ends.

Did this to get the folding table flush with the dining table. Who says medieval history isn’t practical?

Our makeshift table in the living room for dinner/games with family this evening. It passed Lewis’s inspection.