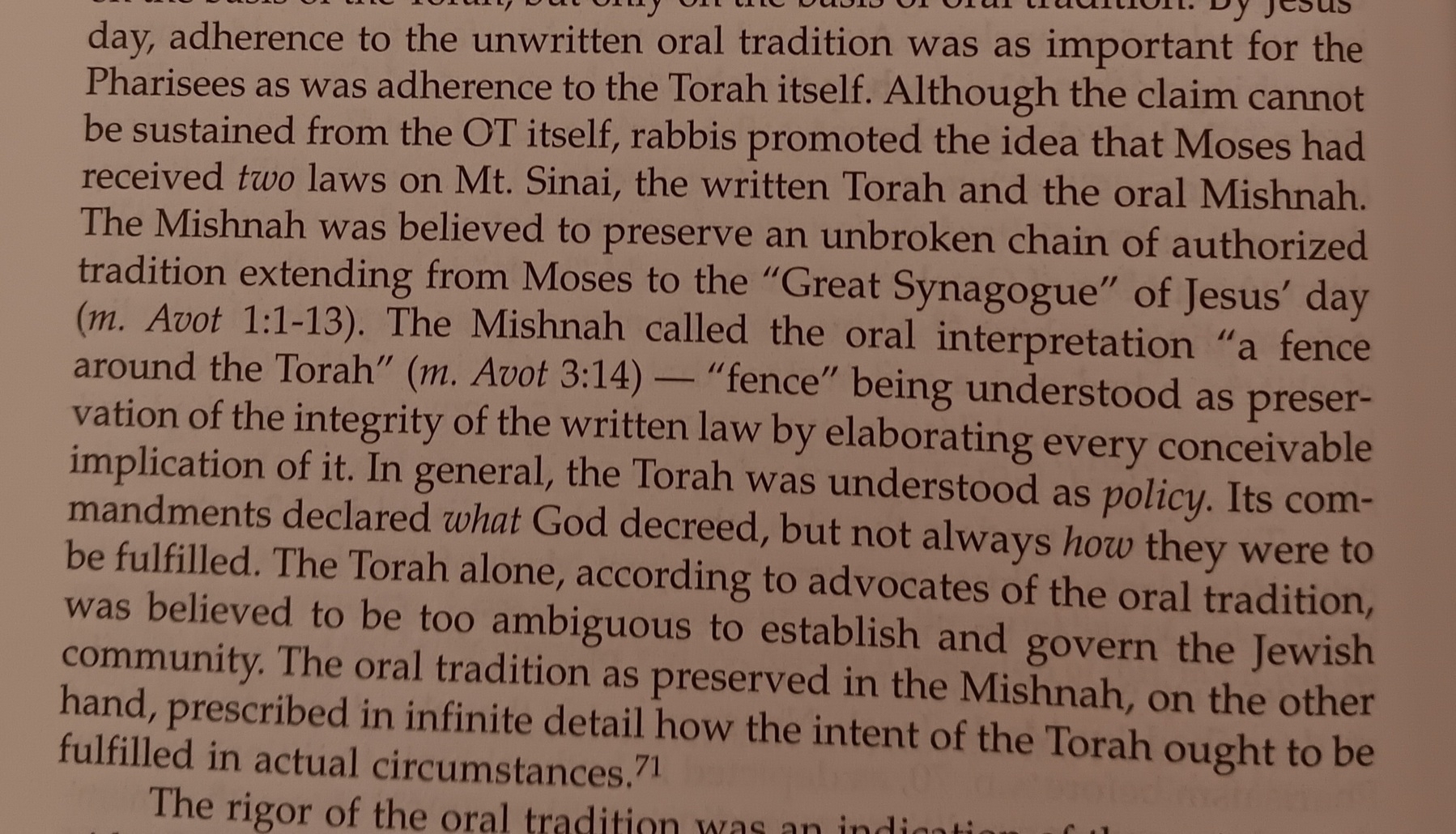

James R. Edwards, commenting on Mark 7 and Jesus’s controversy with the Pharisees and scribes over ritual defilement. Sounds familiar…

James R. Edwards, commenting on Mark 7 and Jesus’s controversy with the Pharisees and scribes over ritual defilement. Sounds familiar…

Trooper was not being especially hospitable to our friend Carlos last night

Lunch with the staff team at Leroy and Lewis

Currently reading: The Virtue of Nationalism by Yoram Hazony 📚

Currently reading: The Insider’s Guide to ADHD by Penny Williams 📚

My family knows the way to my heart

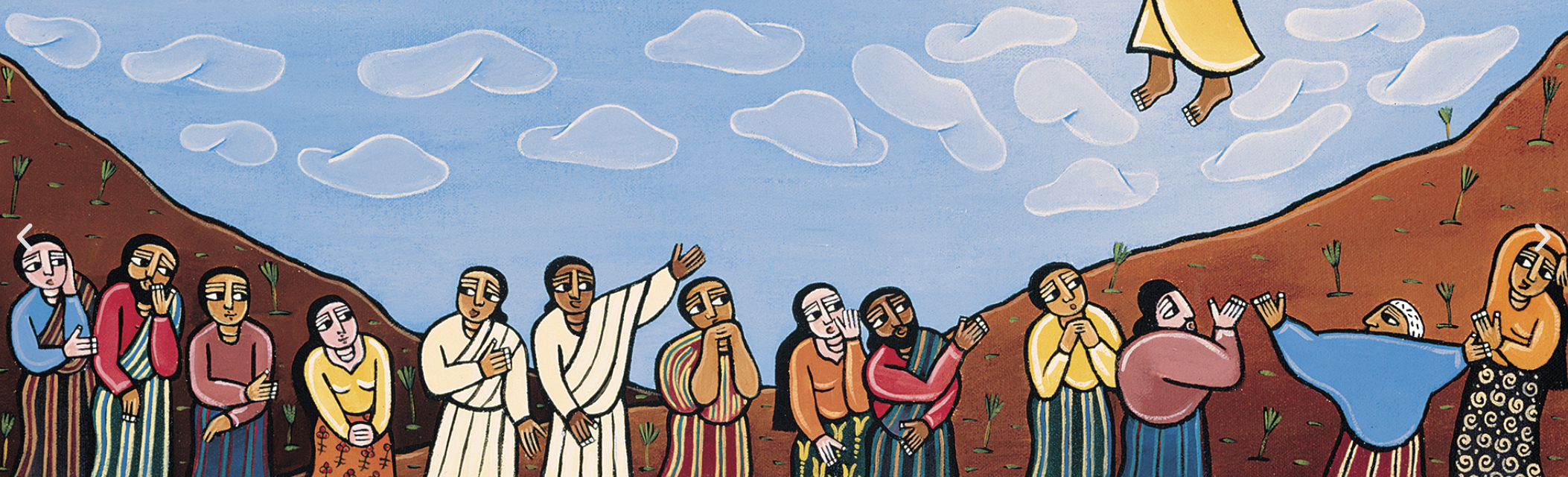

I’m teaching on the Ascension in the morning: an oft-neglected doctrine that’s become increasingly precious to me over the years.

Ascension (2000) by Laura James:

Ascension of Christ (c. 1350) from the Hohenfurth monastery:

dapper fellow

Finished reading: Migrations of the Holy by William T. Cavanaugh 📚

A disjointed book, to be sure: It felt like a collection of previously published essays, which means it didn’t quite cohere into a satisfying whole. BUT, with that caveat out of the way: I would still recommend it to anyone thinking through questions of political theology. Cavanaugh offers trenchant theological analysis of American political culture and the modern nation-state. Though I’m still fuzzy on what it might look like in concrete terms to complexify political space, I am convinced that Cavanaugh is barking up the right tree as it pertains to Christian political engagement.

William T. Cavanaugh, on the “visibility” of the church:

To say that the purpose of the church is to show what human society is supposed to look like is to hold the church to a standard of unity and purity that it has rarely, if ever, accomplished in history. To bind the Holy Spirit to well-performed practices in human history is in effect to banish the Holy Spirit from much of that history. Salvation is visible in a few local instances of faithful churches, mere flotsam on the waves of historical unfaithfulness. […]

What the church makes visible to the world is the whole dynamic drama of sin and salvation, not only the end result of a humanity purified and unified….The church, to put it another way, plays out the tragedy of sin while living in the hope that, in the end, the drama is in reality a comedy and not a tragedy. Sin, then, is not simply to be contrasted with the visibility of the church. The sin of the church is manifest, but it is incorporated into a larger drama of salvation. […]

Sin is an inescapable part of the church in via, just as the cross is an essential part of the drama of salvation. The existence of sinful humanity in the church does not simply impede the redemption that Christ works in human history, but is itself part of the story of that redemption told over and over in the life of the church. As the fruit of the cross, however, the story can only be told in a penitential key. […]

The holiness of the church is visible in its very repentance for its sin. The church is visibly holy not because it is pure, but precisely because it shows to the world what sin looks like. That is, humanity is able to name sin because it has been confronted with the Word of God. The cross is the condition of possibility of sin. It is possible to overemphasize the church’s sinfulness; the church also makes grace visible, in its sacraments and its saints and its social presence among the poor. But the point is that, though sin and grace are countervailing movements in the church, repentance and sanctification are not. […]

The church’s proper response to being taken up into the life of God is not smug assurance of its own purity, but humble repentance for its sin and a constant impulse to reform. In doing so, it must listen to voices from outside the church as well. The church is visible in penance, not in the purity of an ideal social order.