The ideology of the free market now has nothing to limit its claims. There is no visible countervailing power. There seems no sign of a check to its relentless advance. And its destructive potential, both for the coherence of human society and for the safeguarding of the environment, are formidable. The ideology of the free market has proved itself more powerful than Marxism. It is, of course, not just a way of arranging economic affairs. It has deep roots in the human soul. It can be met and mastered only at the level of religious faith, for it is a form of idolatry. The churches have hardly begun to recognize that this is probably their most urgent missionary task during the coming century.

I enjoyed watching Godspeed, and was arrested by this line from Eugene Peterson: “There’s no place on this earth that’s without potential for holiness. Or maybe…the potential for unearthing holiness, right where we are, with these people we are with.”

A deep part of the puzzle of human living is that our desire to be understood and loved is often buried under a fear that if we were seen, the other wouldn’t and couldn’t, looking right at me, say “I love you.” Life is often a cruel combination of “sighing to be approved” (George Herbert) and yet living among others as what Taylor Caldwell calls “sealed vessels” (The Listener). Trapped in this habit of hiding — of shame and secret-keeping — any “I love you” feels like it comes with a footnote: The “you” that is loved is not actually you, but only what Thornton Wilder describes as our poses and “postures before a mirror”: the image we show the world while under the surface hides a lonely, longing, yet still unseen someone.

God’s love is a for-us-as-we-actually-are kind of love. This is one significant implication of God speaking, of the word becoming flesh, of that enfleshed word being promised in bread and wine and water: embodied love that makes contact with actual humans. This love also makes contact with real rather than ideal people through the diagnostic word that unmasks us, that finds us in our hiding, that speaks louder than our lies. To quote Wilder again, he says that what we are gesturing towards when we say art is “true” is that when a painting or poem or song or sculpture encounters us we find ourselves saying, “Oh, that’s the way it really is.” God’s need-unveiling, honesty-evoking love is like that. It reveals what really is. It digs deeper than our denial and reveals that God has “searched me and known me” (Ps. 139), that before this God “all hearts are open, all desires are known, and no secrets are hid” (Collect for Purity). And here — where and when “you” can only mean “you” — the gospel gives the one who “loved me and gave himself for me.”

Thinking with The Alcestiad, you might say that the distinction between law and gospel describes the language God speaks so that those God loves can hear, receive, and experience that love. God unearths our honest need, and so says, “I know you.” And to “you” — with no footnotes — God speaks his first, fundamental, and final word: “I love you.”

Worth revisiting annually: David Zahl’s Eight Theses for Surviving the Internet.

Derek Thompson, arguing that isolated, hyper-online young men are not actually experiencing “a loneliness crisis”:

While I know that some men are lonely, I do not think that what afflicts America’s young today can be properly called a loneliness crisis. It seems more to me like an absence-of-loneliness crisis. It is a being-consantly-alone-and-not-even-thinking-that’s-a-problem crisis. Americans—and young men, especially—are choosing to spend historic gobs of time by themselves without feeling the internal cue to go be with other people, because it has simply gotten too pleasurable to exist without them. […]

When porn seems less fraught than sexual partners, and when late night parties seem lower status than early-morning Pilates, a toxic asceticism is spreading throughout American life. No, the problem is not loneliness. The problem is that we’ve forgotten how to feel lonely in the first place.

The whole essay is chilling and well worth your time. The only part I tripped over was Thompson calling these hyper-online young men “the monks in the casino” (which is the title of the essay). His point is easy enough to grasp: “monks” because isolated and cut off from social life; “in the casino” because addicted to the stimulation of online porn and gambling. But I just kept thinking about the monks at Monte Cassino. Oh well.

Matthew Burdette, describing why Christian faith feels elusive today:

My most profound flashes of doubt in the existence of God…have been at church. I’ve sat with philosophical arguments against the existence of God, but none have had the same force as sitting in church and being overwhelmed by the feeling that nothing being said matters, the feeling that the church’s very life screams, “We don’t take this stuff too seriously." […]

The vexing puzzle of the Christian experience today is that our talk of God seems biblical and therefore difficult to indict for idolatry, but it has lost its gravity. We are theoretically in proximity to its object, but it exerts no force on us. Even if we keep showing up or keep identifying ourselves as Christians, we find it harder and harder to articulate the necessity and unconditional importance of this faith. It is as though we have settled for an idol.

The reason for this elusiveness? According to Burdette, it stems from a crisis of authority:

The Christian faith is elusive today because the authority of Christian ministry—lay and ordained, word and action—is no longer authoritative. The salt has lost its saltiness. Assertions of ecclesiastical (and, relatedly, biblical) authority today amount to telling people not to trust the evidence of their own experience: some will comply, but most will not. Those who have found a way to hope against hope, to hold fast to faith despite feeling adrift, must move beyond the ease of having the right theological answers and overcome the defensiveness that comes with saying that widespread faithlessness is a ministerial and homiletical problem—that it is our fault. The question Christians must find a way to answer is why we have lost our authority and whether it is recoverable.

Burdette goes on to list four primary ways that the church has compromised its authority. First, “unseriousness”:

I said earlier that my own flashes of doubt have taken place in church, in response to the communication of unseriousness, that what is taking place does not matter. Churches habitually give in to the temptation to amuse, entertain, and trivialize what’s taking place in Christian worship. Church activities, frequently targeted to families with children, are often indistinguishable from what’s on offer at public libraries. Pet blessings fall into this category: “The Creator of the universe became flesh and died for your salvation—but, yes, by all means, bring your dog to church so those commissioned to preach the gospel can tell him he’s a good boy.” But the truly corrosive forms of unseriousness are subtler. For example, the well-intended trend in my denomination, the Episcopal Church, to admit unbaptized persons to Holy Communion unavoidably robs both baptism and the Eucharist of gravity. It is also common for never-before-seen parents to present never-to-be-seen-again babies to be baptized, and by being too nice to refuse such parents, the church’s ministers tell its members that baptism is not actually initiation and that the church is a place where promises needn’t be kept. The church is a creature of the Word and sacrament: What happens when the church fosters a culture where words don’t matter? A haunting question to consider in view of the quality of much Christian preaching today.

Second, “illicit innovation”:

Where words do not matter, neither can order. Where there is not seriousness, there cannot be a spirit of stewardship; and where the church’s ministers and members see themselves as proprietors rather than stewards, they are no longer answerable to tradition, nor inhibited from unauthorized innovation. But all human authority simply is stewardship.

Third, “an inattention to how most people experience reality that ensures the Christian message does not ring true”:

For most people today, the church’s historic teachings on sexuality and the human body are confusing (at best) and do not ring true. Which is to say, they have lost their authority. A faith that does not ring true, especially in the areas of life most precious to us, is a faith that doesn’t matter for real life. Any religious life that is devoid of a compelling claim to ultimacy is at best a hobby, perhaps useful as a way to meet other people and to pass the time. It cannot command ultimate concern. The only way for the Christian message to command ultimate concern is for it to be shown to make sense of life’s preliminary concerns. Morally traditional Christians must find ways to convey the whole truth of the Christian faith to the facets of life where it currently rings false.

Fourth (and finally), “schism”:

Unlike immediately after the Protestant Reformation, almost all Christians today are happy to affirm that Protestants or Catholics or the Orthodox are truly Christians—and are thereby burdened to explain why their differences actually matter. The partial success but overall failure of the modern ecumenical movement has meant that many members of churches, especially Protestant, have become fundamentally post-denominational in their outlook. When churches can acknowledge that other churches from whom they are separated are equally valid as Christian churches, but don’t overcome the actual divisions, the unintended message is that the divisions are evidently not so theologically important after all, and the result is a church culture of consumer choice about where to worship and what to believe. But a faith decision based on preference is no faith decision at all—it permits no authority. The agony of those with faith is to respond to authority in this situation of choice.

His conclusion is worth quoting at length:

In each of these instances the church’s ministers and members must renew contact with the overwhelming gravity that pulled them into faith—to reorient themselves to the church’s foundation and founding. Ecumenically, the difficult task is to struggle toward Christian unity by means of serious theological conflict, not softening differences between Christians but bearing the grief of highlighting them. Similarly, for the Christian ministry to inspire faith, it must act with courage and attentiveness in its actual situation, not at a remove from life, where the faith is meant to be true. This courage requires confidence in the tradition as it has been handed down: the only possibility of authority in the church today is that those who had authority yesterday are still permitted to speak.

And finally, such speaking will have an effect only if Christian words matter. While I have felt doubt because of unseriousness, I have also been inspired to deeper faith when I have heard it expressed with grave seriousness. When I can trust a minister to speak plainly about the severity of sin, only then are words of absolution and the assurance of God’s love comforting and effective. Preaching, too, must find its way back to the foundation. The best preaching advice I ever received was from the theologian Robert Jenson, whose words to me serve well as a conclusion: If by the end of your sermon you can’t say, “Thus says the Lord,” you will have wasted everyone’s time. For faith to wield true authority, every Christian must learn to speak in such a way that it may truly be said: thus says the Lord.

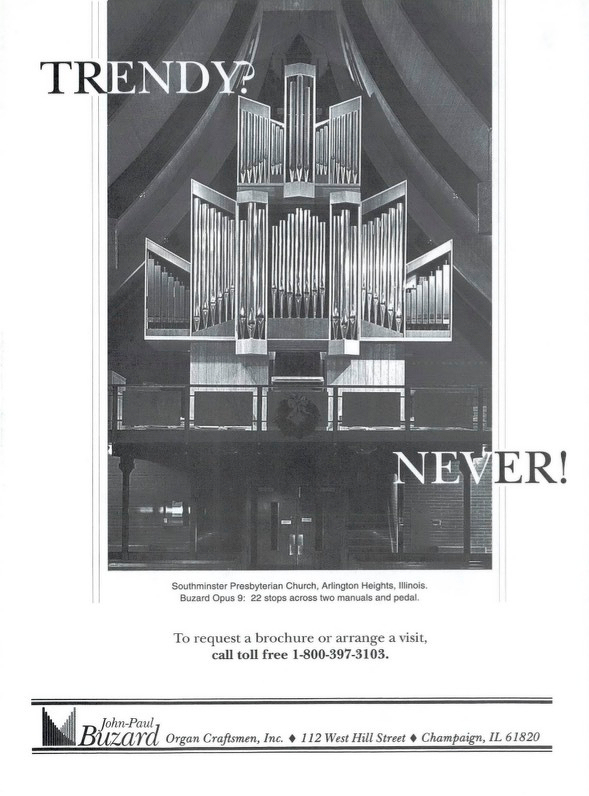

I’m loving the trad energy of this 1993 ad from The American Organist. Also, it appears Buzard Pipe Organ Builders is still in business; good for them!

Finished reading: Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson 📚

Finished reading: The Edge of Words by Rowan Williams 📚

A stunning, mind-bending achievement. There is immense apologetic value here, though it is not straightforwardly a work of apologetics. Indeed, the best comparison to Williams' argument (at least, the one that comes immediately to mind) is from David Bentley Hart’s The Experience of God. Neither author argues directly for the existence of God, yet both books provide rather powerful (if oblique) arguments for God’s existence. Hart’s argument focuses on three “moments” in our experience of reality (being, consciousness, bliss) as pointers to the fundamental reality of God. Williams, meanwhile, focuses on language, particularly the peculiarities of language. I’m no prophet, but I can say with confidence that I’ll be reading Rowan Williams for the rest of my life.

Jesus appears to have taken no steps to embody his teaching about the kingdom in a written form, which would be insulated against distortion by the fallible memories of his disciples. The Christian church possesses nothing comparable to the Qur’an. The teaching of Jesus has come to us in varied versions filtered through the varied remembering and interpretings of different groups of believers. What, on the other hand, did occupy the center of Jesus' concern was the calling and binding to himself of a living community of men and women who would be the witnesses of what he was and did. The new reality that he introduced into history was to be continued through history in the form of a community, not in the form of a book.

It’s easy for Protestants (like me) to balk at what Newbigin says here about Scripture, leading us to then tune out the rest. But I do think he’s making a really important point about Jesus calling “a living community of men and women” to be his witnesses—a community that exists in history and extends across history. Newbigin’s point is that Jesus cared supremely about equipping his disciples (and, by extension, the church) for the task of bearing the presence of God’s kingdom through history. To be sure, Scripture plays an absolutely essential role in that whole process. But there is an unavoidably visible, tangible reality to the church (as the community of Jesus in time) that we can see and point to and trace its development (and declensions) and submit to and so on. This is what, in another context, I referred to (drawing on Richard John Neuhaus) as being an “ecclesial Christian.”