In Christ’s incarnation all of humanity regains the dignity of bearing the image of God. Whoever from now on attacks the least of the people attacks Christ, who took on human form and who in himself has restored the image of God for all who bear a human countenance. In community with the incarnate one, we are once again given our true humanity. With it, we are delivered from the isolation caused by sin, and at the same time restored to the whole of humanity. Inasmuch as we participate in Christ, the incarnate one, we also have a part in all of humanity, which is borne by him. Since we know ourselves to be accepted and borne within the humanity of Jesus, our new humanity now also consists in bearing the troubles and the sins of all others. The incarnate one transforms his disciples into brothers and sisters of all human beings. The “philanthropy” (Titus 3:4) of God that became evident in the incarnation of Christ is the reason for Christians to love every human being on earth as a brother or sister. The form of the incarnate one transforms the church-community into the body of Christ upon which all of humanity’s sin and trouble fall, and by which alone these troubles and sins are borne.

newest addition to the living room

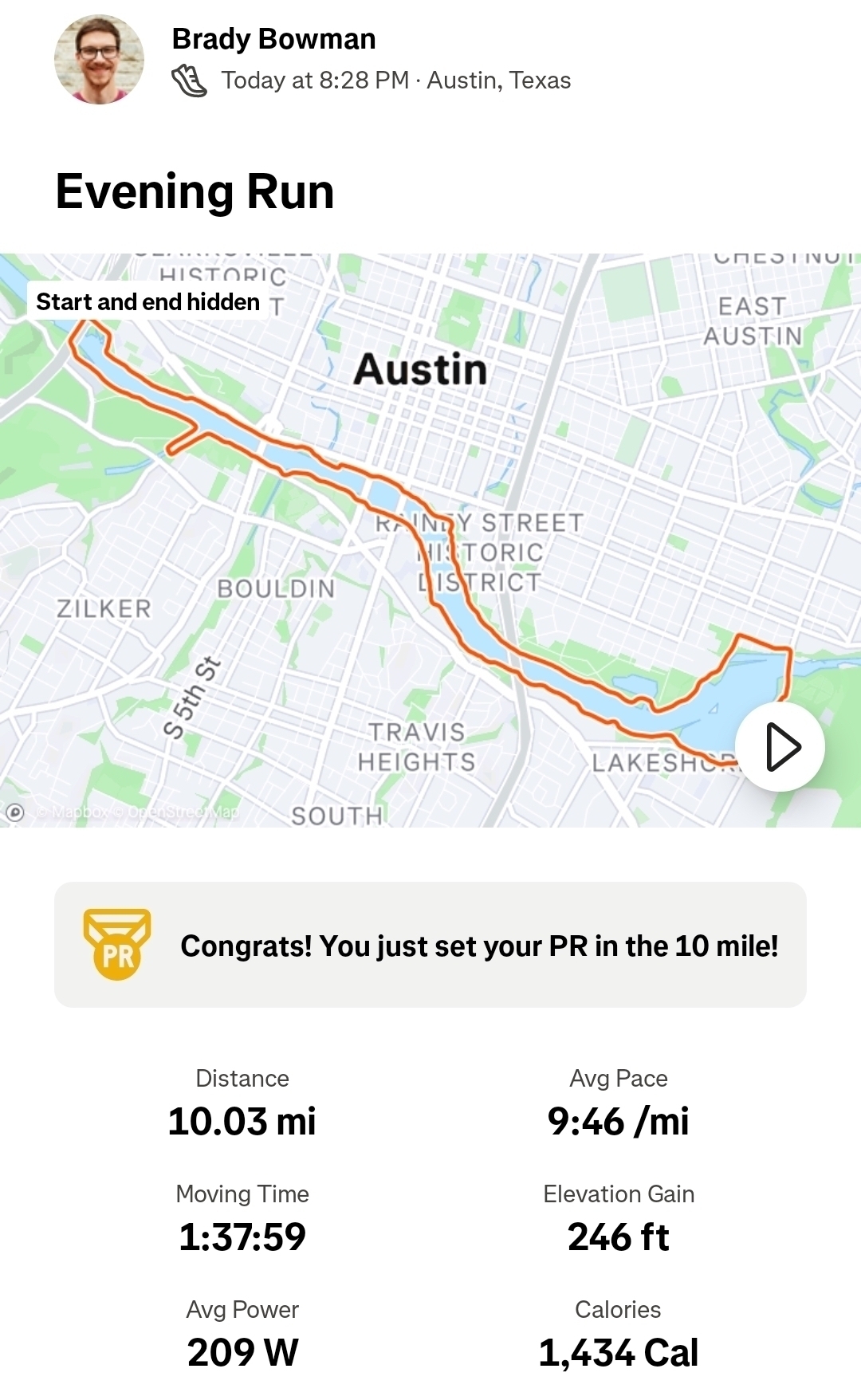

Crossed the ten-mile threshold for the first time last night! (my knees are sore this morning)

Finished reading: 8 Hours or Less by Ryan Huguley 📚

I usually avoid this kind of book like the plague, but I actually found it really useful. I don’t think I’ll get my prep down to eight hours any time soon (or probably ever). Even so, Huguley’s book is mainly helpful in providing a weekly process for sermon writing.

currently listening: Mood Ring by Joan Shelley

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, on the difference between “works” and “fruit” in Galatians 5:

The “works” of the flesh are many, but there is only one “fruit” of the Spirit. Works are accomplished by human hands, but the fruit sprouts and grows without the tree knowing it. Works are dead, but fruit is alive and the bearer of seeds which themselves produce new fruit. Works can exist on their own, but fruit cannot exist without a tree. Fruit is always something full of wonder, something that has been created. It is not something willed into being, but something that has grown organically. The fruit of the Spirit is a gift of which God is the sole source. Those bearing this fruit are as unaware of it as a tree is of its fruit. The only thing they are aware of is the power of the one from whom they receive their life. There is no room for praise here, but only the ever more intimate union with the source, with Christ. The saints themselves are unaware of the fruit of sanctification they bear. The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, arguing that Christian sanctification requires identification with the visible church-community:

A merely personal sanctification which seeks to bypass [the] openly visible separation of the church-community from the world confuses the pious desires of the religious flesh with the sanctification of the church-community, which has been accomplished in Christ’s death and is being actualized by the seal of God. It is the deceptive pride and the false spiritual desire of the old, sinful being that seeks to be holy apart from the visible community of Christians. Contempt for the body of Christ as the visible community of justified sinners is what is really hiding behind the apparent humility of this kind of inwardness. It is indeed contempt for the body of Christ, since Christ was pleased visibly to assume my flesh and to carry it to the cross. It is contempt for the community, since I seek to be holy apart from other Christians. It is contempt for sinners, since in self-bestowed holiness I withdraw from my church in its sinful form. Sanctification apart from the visible church-community is mere self-proclaimed holiness.

Whatever the disciples do, they do it within the communal bond of the community of Jesus and as its members. Even the most secular act now takes place within the bounds of the church-community. This then is valid for the body of Christ: where one member is, there is also the whole body, and where the body is, there is also the member. There is no area of life where the member would be allowed or would even want to be separated from the body. Wherever one member happens to be, whatever one member happens to do, it always takes place “within the body,” within the church-community, “in Christ.” Life as a whole is taken up “into Christ.”