Early Sunday Morning (1930) by Edward Hooper:

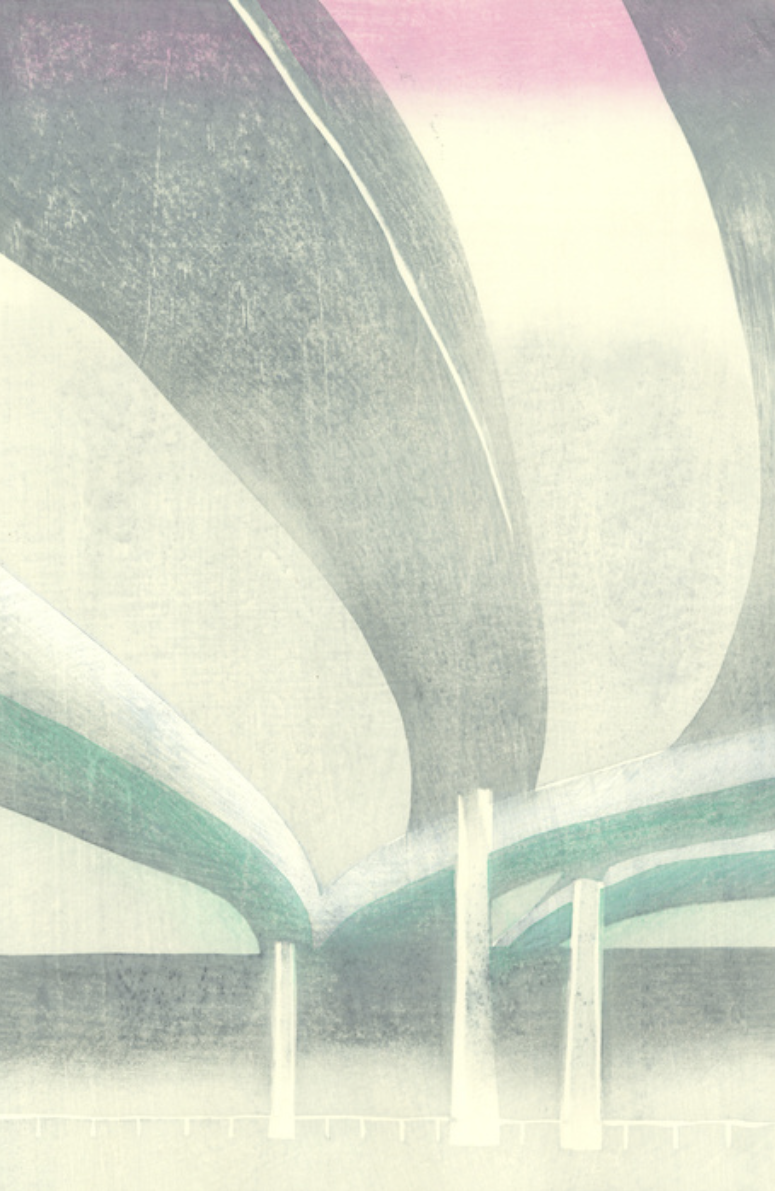

Overpasses (2.2) (2022) by Raluca Iancu:

In the unwinding, everything changes and nothing lasts, except for the voices, American voices, open, sentimental, angry, matter-of-fact; inflected with borrowed ideas, God, TV, and the dimly remembered past—telling a joke above the noise of the assembly line, complaining behind window shades drawn against the world, thundering justice to a crowded park or an empty chamber, closing a deal on the phone, dreaming aloud late at night on a front porch as trucks rush by in the darkness.

Alone on a landscape without solid structures, Americans have to improvise their own destinies, plot their own stories of success and salvation. A North Carolina boy clutching a Bible in the sunlight grows up to receive a new vision of how the countryside could be resurrected. A young man goes to Washington and spends the rest of his career trying to recall the idea that drew him there in the first place. An Ohio girl has to hold her life together as everything around her falls apart, until, in middle age, she finally seizes the chance to do more than survive.

As these obscure Americans find their way in the unwinding, they pass alongside new monuments where the old institutions once stood—the outsized lives of their most famous countrymen, celebrities who only grow more exalted as other things recede. These icons sometimes occupy the personal place of household gods, and they offer themselves as answers to the riddle of how to live a good or better life.

The unwinding brings freedom, more than the world has ever granted, and to more kinds of people than ever before—freedom to go away, freedom to return, freedom to change your story, get your facts, get hired, get fired, get high, marry, divorce, go broke, begin again, start a business, have it both ways, take it to the limit, walk away from the ruins, succeed beyond your dreams and boast about it, fail abjectly and try again. And with freedom the unwinding brings its illusions, for all these pursuits are as fragile as thought balloons popping against circumstances. Winning and losing are all-American games, and in the unwinding winners win bigger than ever, floating away like bloated dirigibles, and losers have a long way to fall before they hit bottom, and sometimes they never do.

This much freedom leaves you on your own. More Americans than ever before live alone, but even a family can exist in isolation, just managing to survive in the shadow of a huge military base without a soul to lend a hand. A shiny new community can spring up overnight miles away from anywhere, then fade away just as fast. An old city can lose its industrial foundation and two-thirds of its people, while all its mainstays—churches, government, businesses, charities, unions—fall like building flats in a strong wind, hardly making a sound.

If you were born around 1960 or afterward, you have spent your adult life in the vertigo of that unwinding. You watched structures that had been in place before your birth collapse like pillars of salt across the vast visible landscape—the farms of the Carolina Piedmont, the factories of the Mahoning Valley, Florida subdivisions, California schools. And other things, harder to see but no less vital in supporting the order of everyday life, changed beyond recognition—ways and means in Washington caucus rooms, taboos on New York trading desks, manners and morals everywhere. When the norms that made the old institutions useful began to unwind, and the leaders abandoned their posts, the Roosevelt Republic that had reigned for almost half a century came undone. The void was filled by the default force in American life, organized money.

No one can say when the unwinding began—when the coil that held Americans together in its secure and sometimes stifling grip first gave way. Like any great change, the unwinding began at countless times, in countless ways—and at some moment the country, always the same country, crossed a line of history and became irretrievably different.

Currently reading: Christ-Centered Preaching by Bryan Chapell 📚