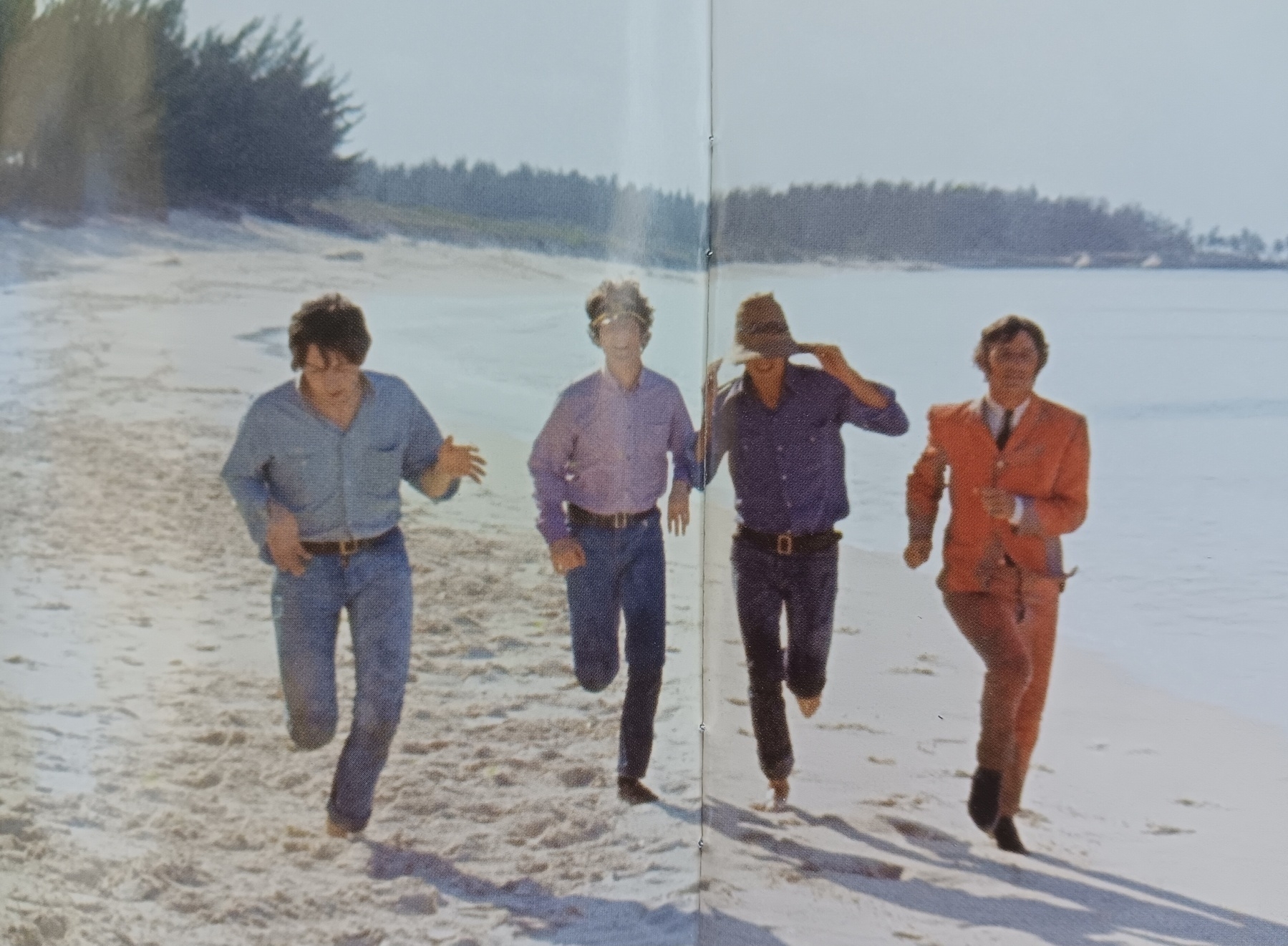

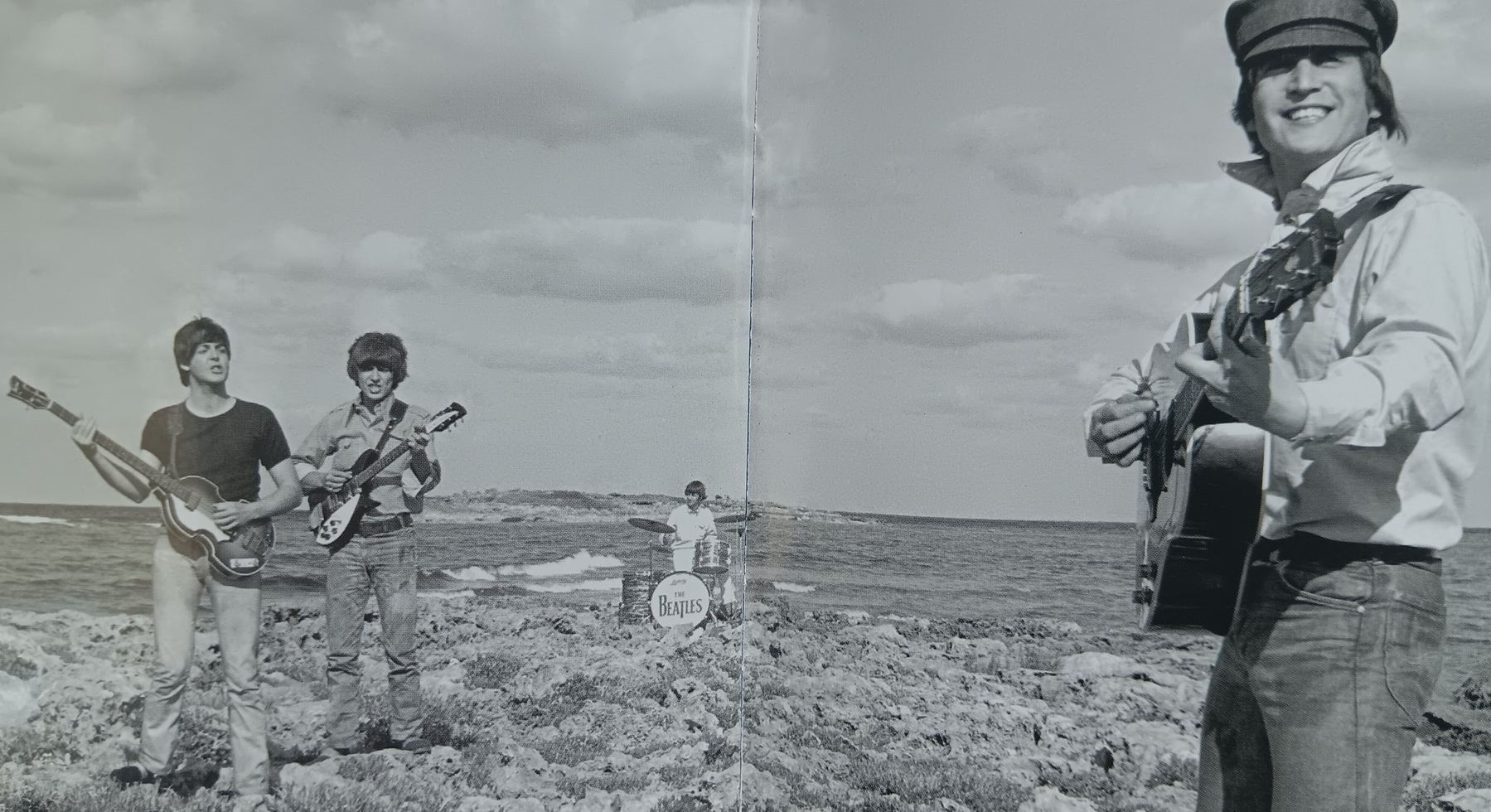

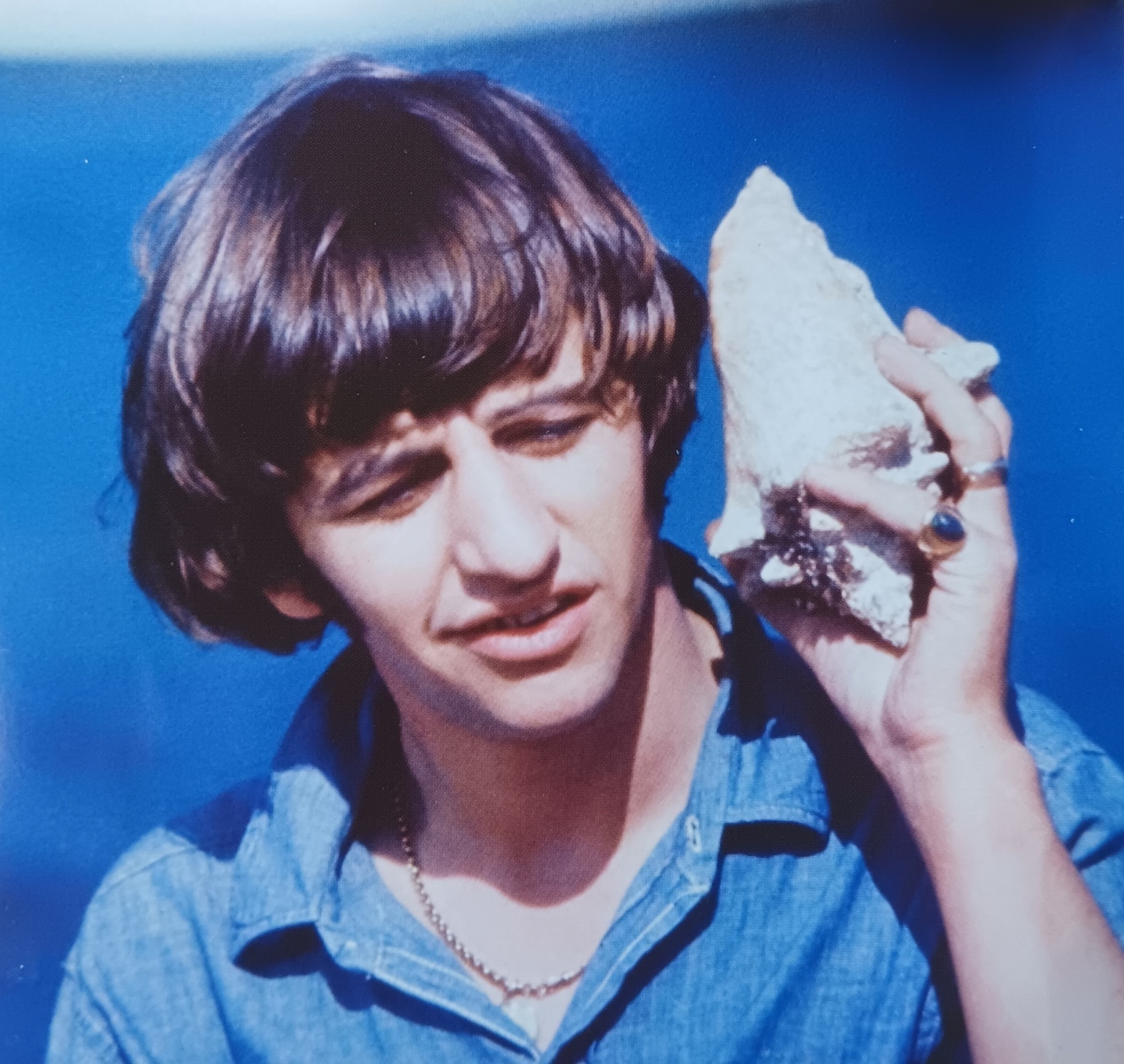

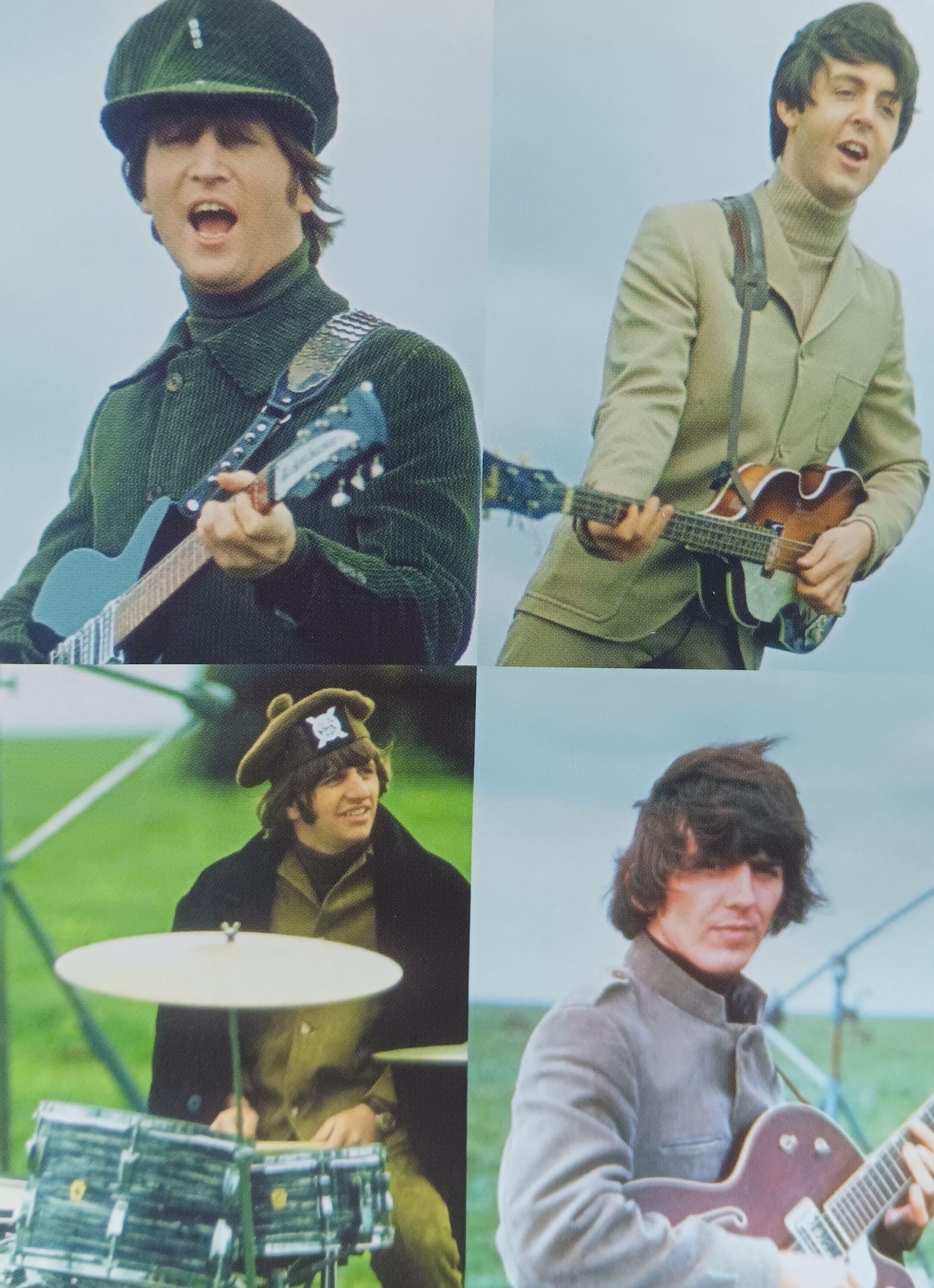

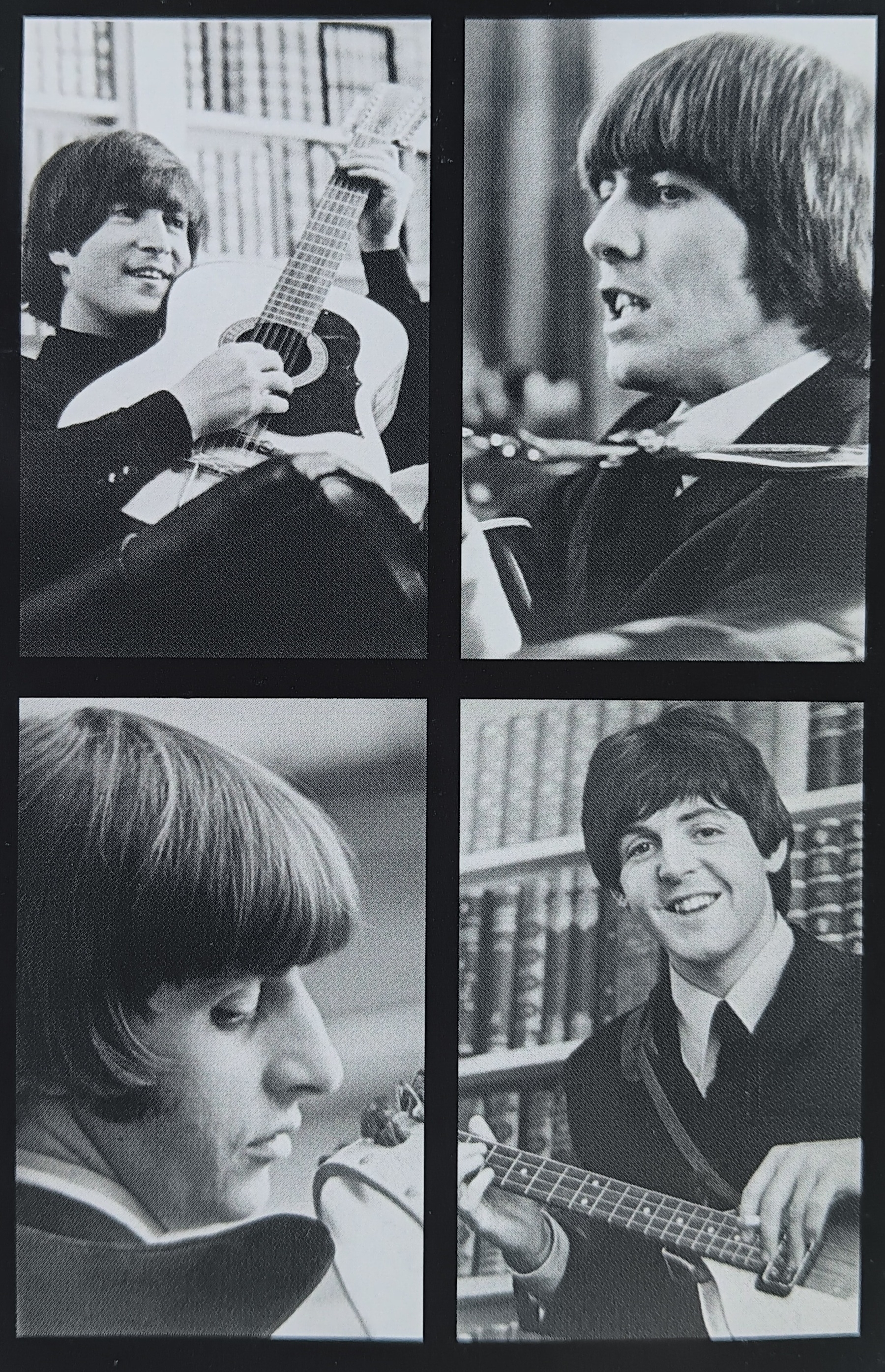

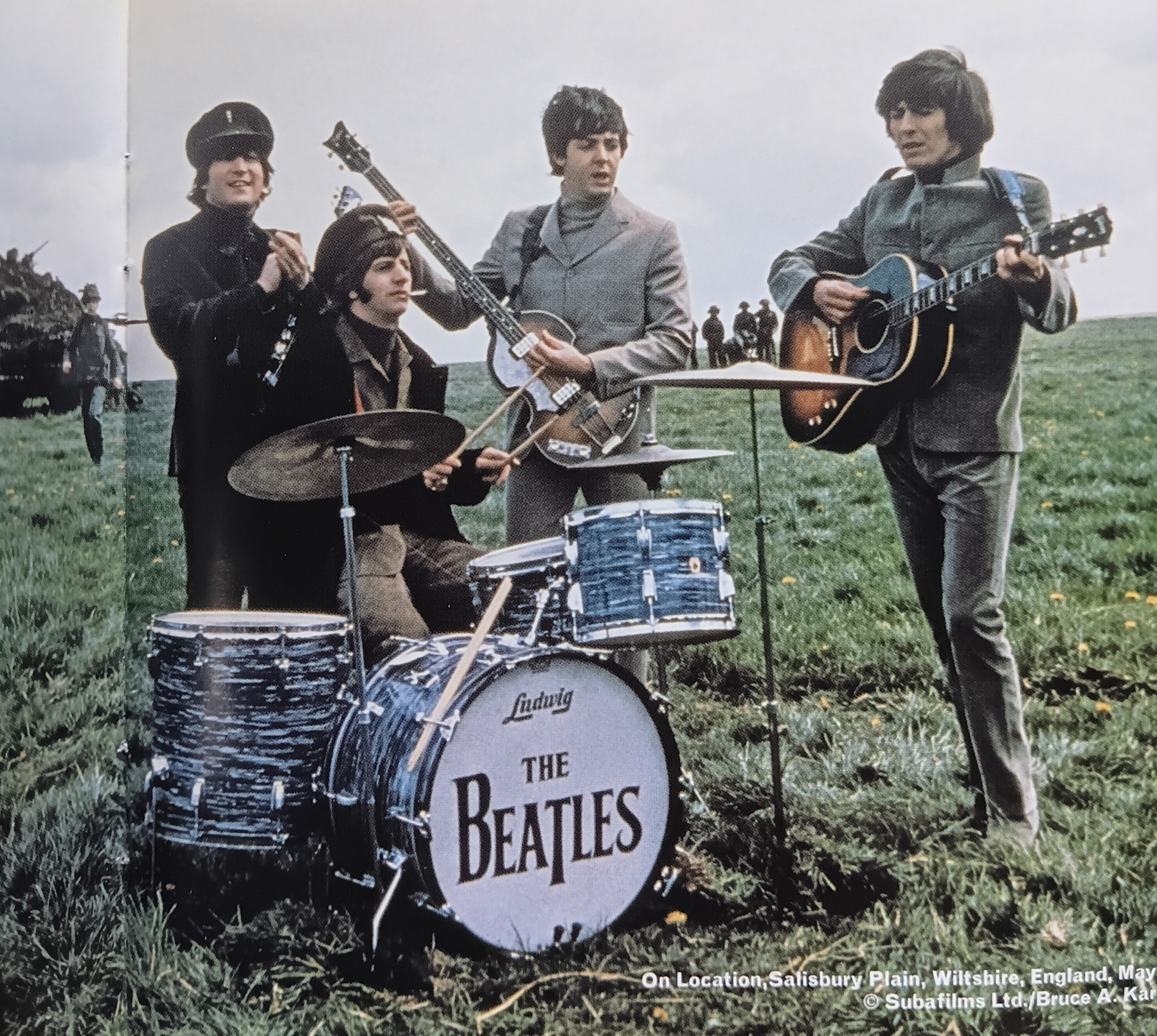

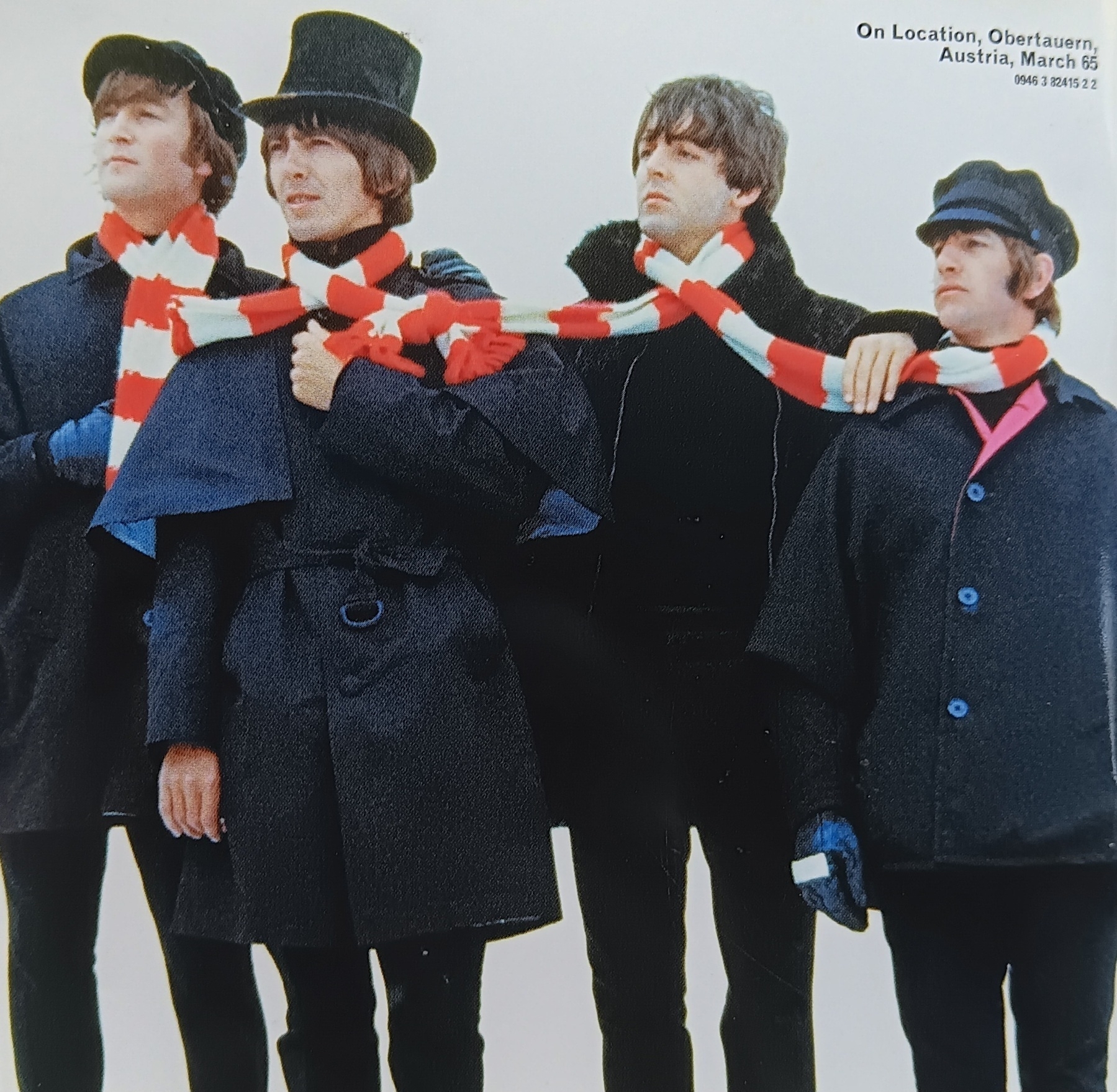

currently listening: Help! by the Beatles

rooftop

Finished reading: Preaching That Moves People by Yancey Arrington 📚

Really helpful book on an under-appreciated aspect of preaching: the emotional impact of sermons. In other words, this book is more about connecting with congregants than with drafting content that’s technically correct. I’ve been wanting more help on this score. Highly recommended.

Currently reading: Preaching That Moves People by Yancey Arrington 📚

Currently reading: Saving Eutychus by Gary Millar and Phil Campbell 📚

Finished reading: The Silver Chair by C. S. Lewis 📚