Miroslav Volf, describing the communal analogue to his notion of a “catholic personality”—namely, a “catholic community”:

No church in a given culture may isolate itself from other churches in other cultures declaring itself sufficient to itself and to its own culture. Every church must be open to all other churches. We often think of a local church as a part of the universal church. We would do well also to invert the claim. Every local church is a catholic community because, in a profound sense, all other churches are a part of that church, all of them shape its identity. As all churches together form a world-wide ecumenical community, so each church in a given culture is a catholic community. Each church must therefore say, “I am not only I; all other churches, rooted in diverse cultures, belong to me too.” Each needs all to be properly itself.

Miroslav Volf, unpacking what he calls a “catholic personality”:

When God comes, God brings a whole new world. The Spirit of God breaks through the self-enclosed worlds we inhabit; the Spirit re-creates us and sets us on the road toward becoming what I like to call a “catholic personality,” a personal microcosm of the eschatological new creation. A catholic personality is a personality enriched by otherness, a personality which is what it is only because multiple others have been reflected in it in a particular way. The distance from my own culture that results from being born by the Spirit creates a fissure in me through which others can come in. The Spirit unlatches the doors of my heart saying: “You are not only you; others belong to you too.”

A genuinely Christian reflection on social issues must be rooted in the self-giving love of the divine Trinity as manifested on the cross of Christ; all the central themes of such reflection will have to be thought through from the perspective of the self-giving love of God.

How much “Christian” reflection on social issues fails to meet this standard? It’s worth pondering what categories or images tend to dominate in our cultural analysis. The self-giving love of God—that seems like it ought to be pretty central, yeah?

Miroslav Volf, explaining why he chooses to focus more on social agents than social arrangements (would that other theologians/pastors/etc followed his example):

Why am I forgoing a discussion of social arrangements? Put very simply, though I have strong preferences, I have no distinct proposal to make. I am not sure even that theologians qua theologians are the best suited to have one. My point is not that Christian faith has no bearing on social arrangements. It manifestly does. Neither is my point that reflection on social arrangement is unimportant, a view sometimes advocated on the fallacious grounds that social arrangements will take care of themselves if we have the right kind of social agents. Attending to social arrangements is essential. But it is Christian economists, political scientists, social philosophers, etc. in cooperation with theologians, rather than theologians themselves, that ought to address this issue because they are best equipped to do so—an argument Nicholas Wolterstorff has persuasively made in his essay “Public Theology or Christian Learning” (Wolterstorff 1996). When not acting as helpmates of economists, political scientists, social philosophers, etc.—and it is part of their responsibility to act as this way—theologians should concentrate less on social arrangements and more on fostering the kind of social agents capable of envisioning and creating just, truthful, and peaceful societies, and on shaping a cultural climate in which such agents will thrive.

Currently reading: Exclusion & Embrace by Miroslav Volf 📚

Finished reading: Saving Eutychus by Gary Millar and Phil Campbell 📚

One of those books that I’ve heard referenced enough times that I felt like I already knew the basic insights. Even so, still a very useful primer on preaching.

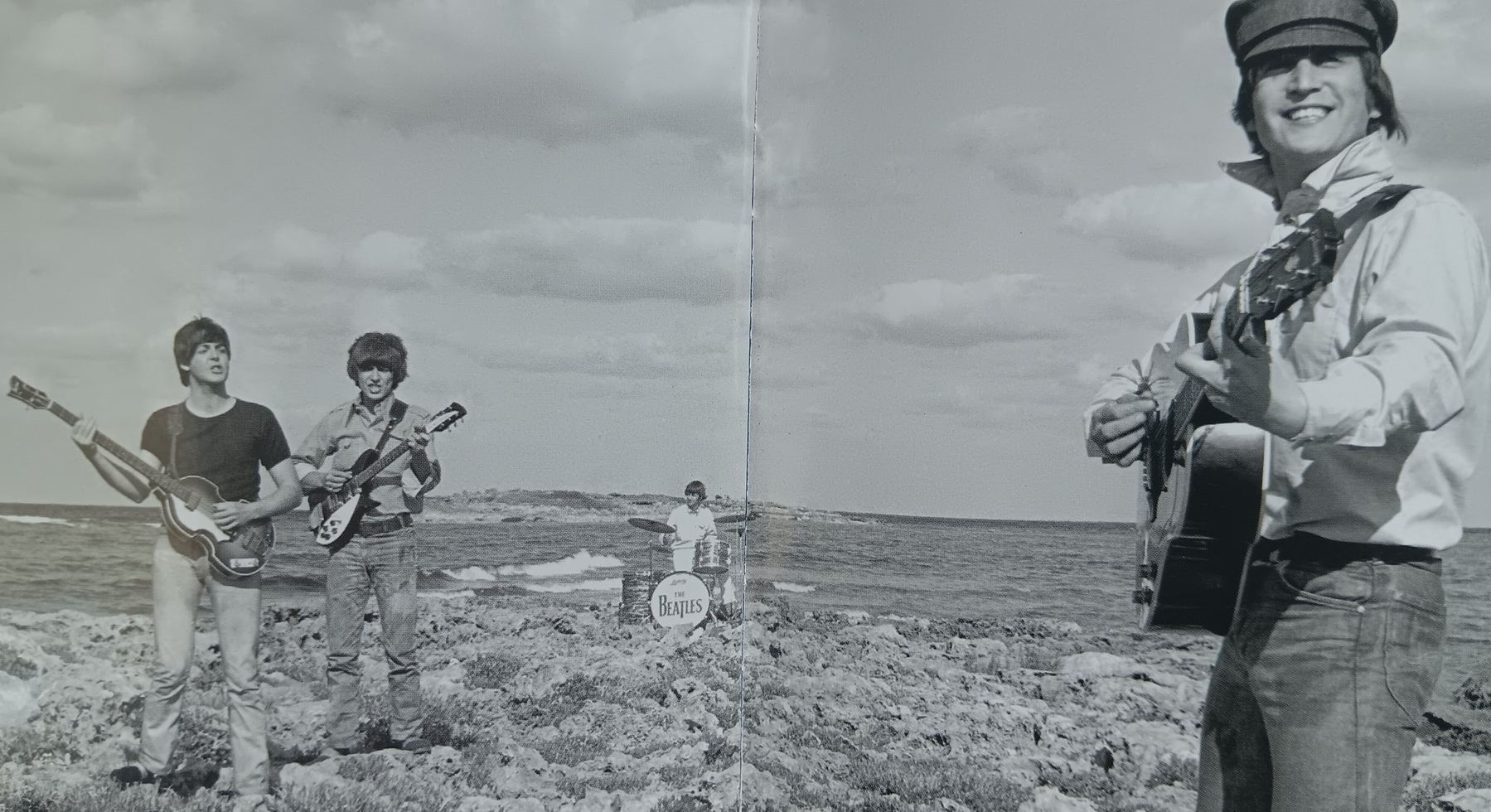

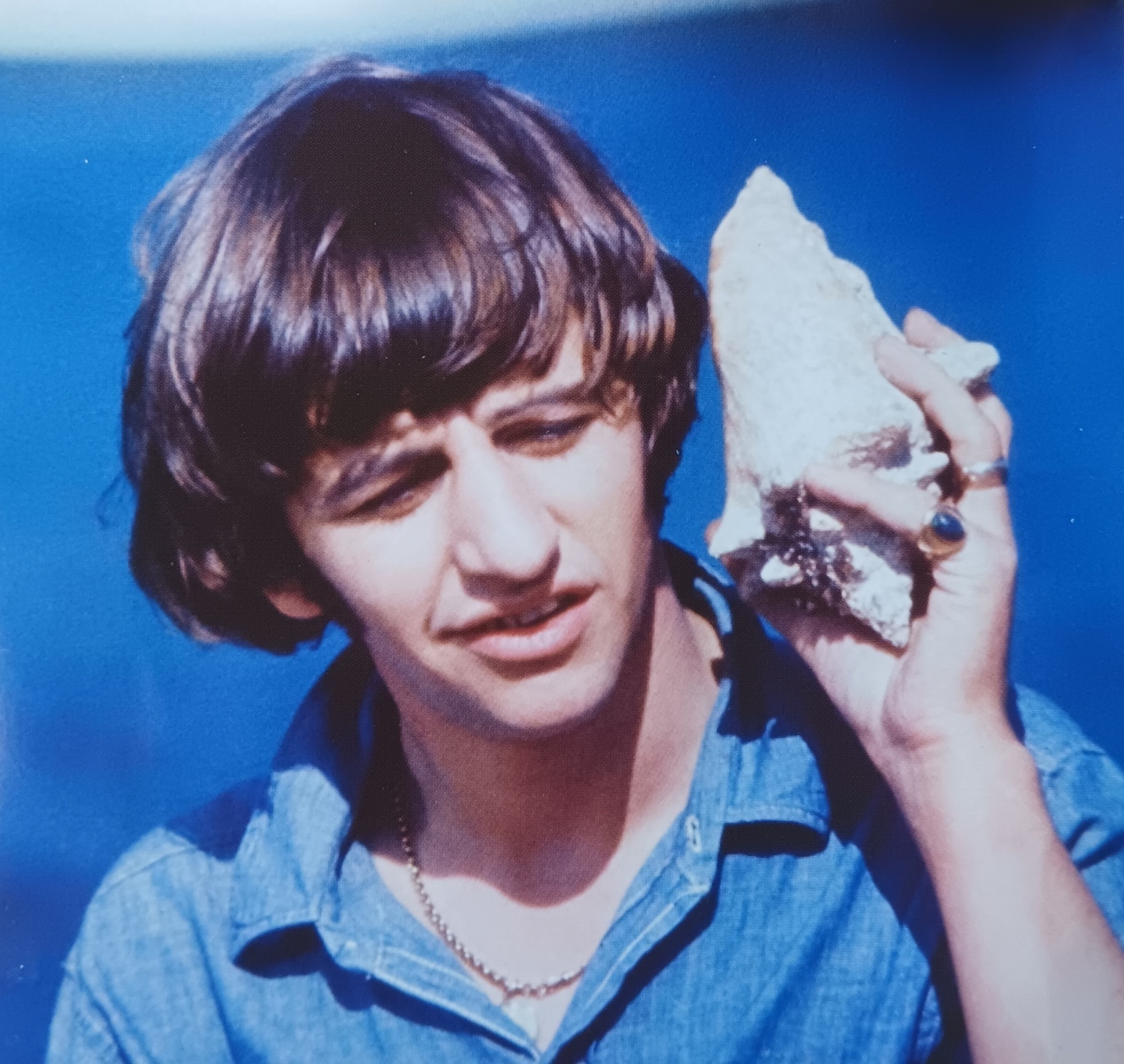

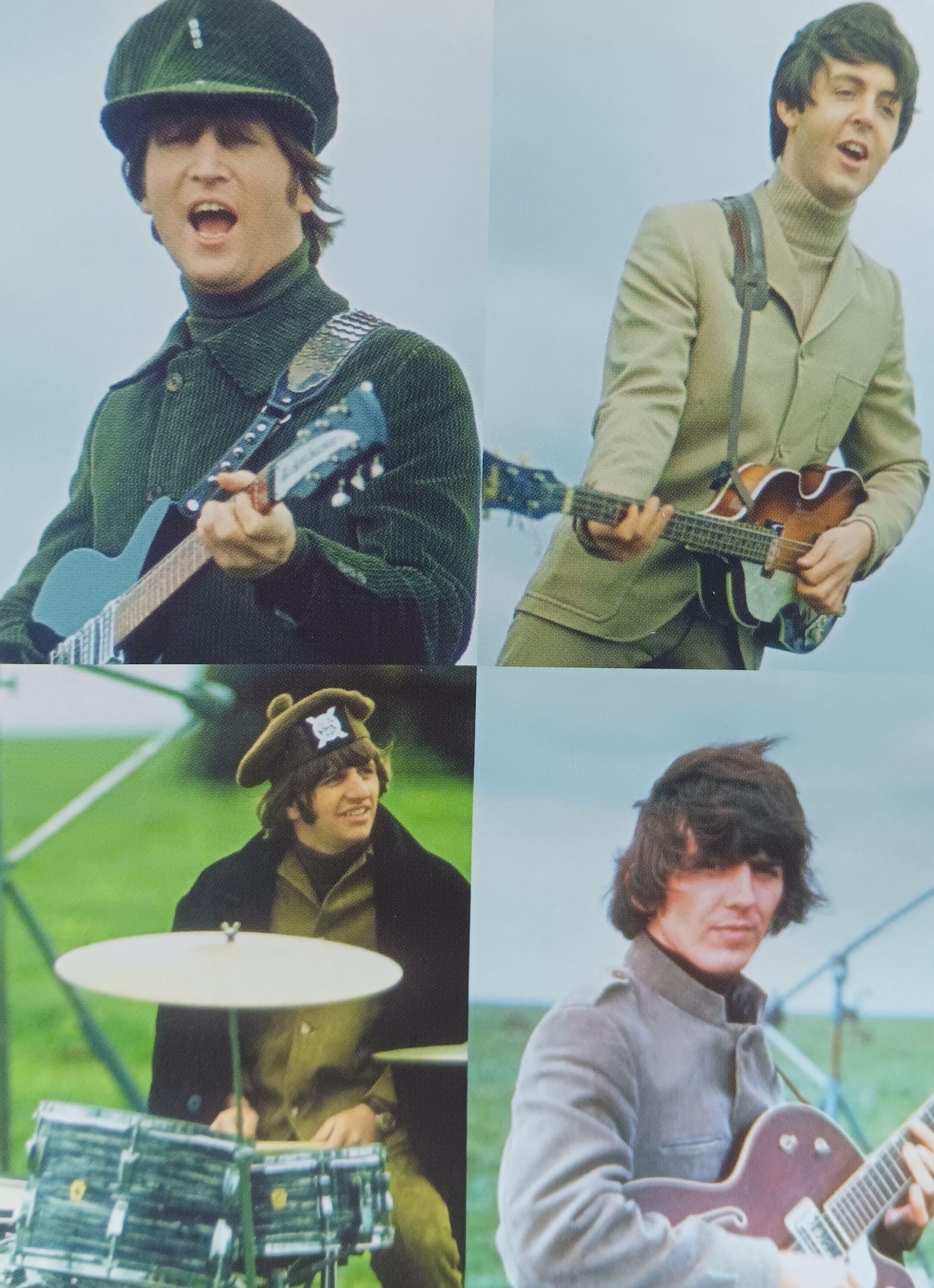

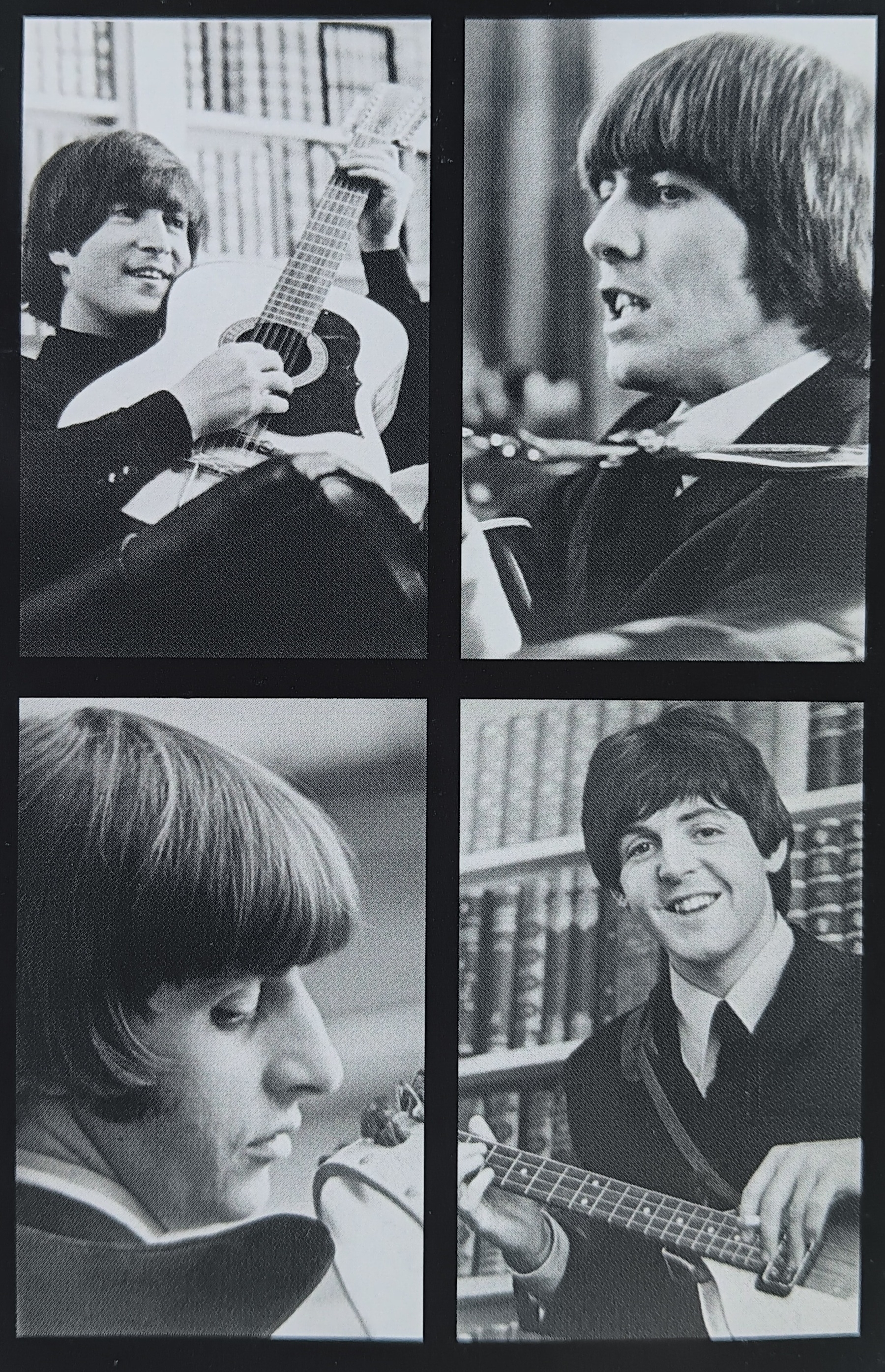

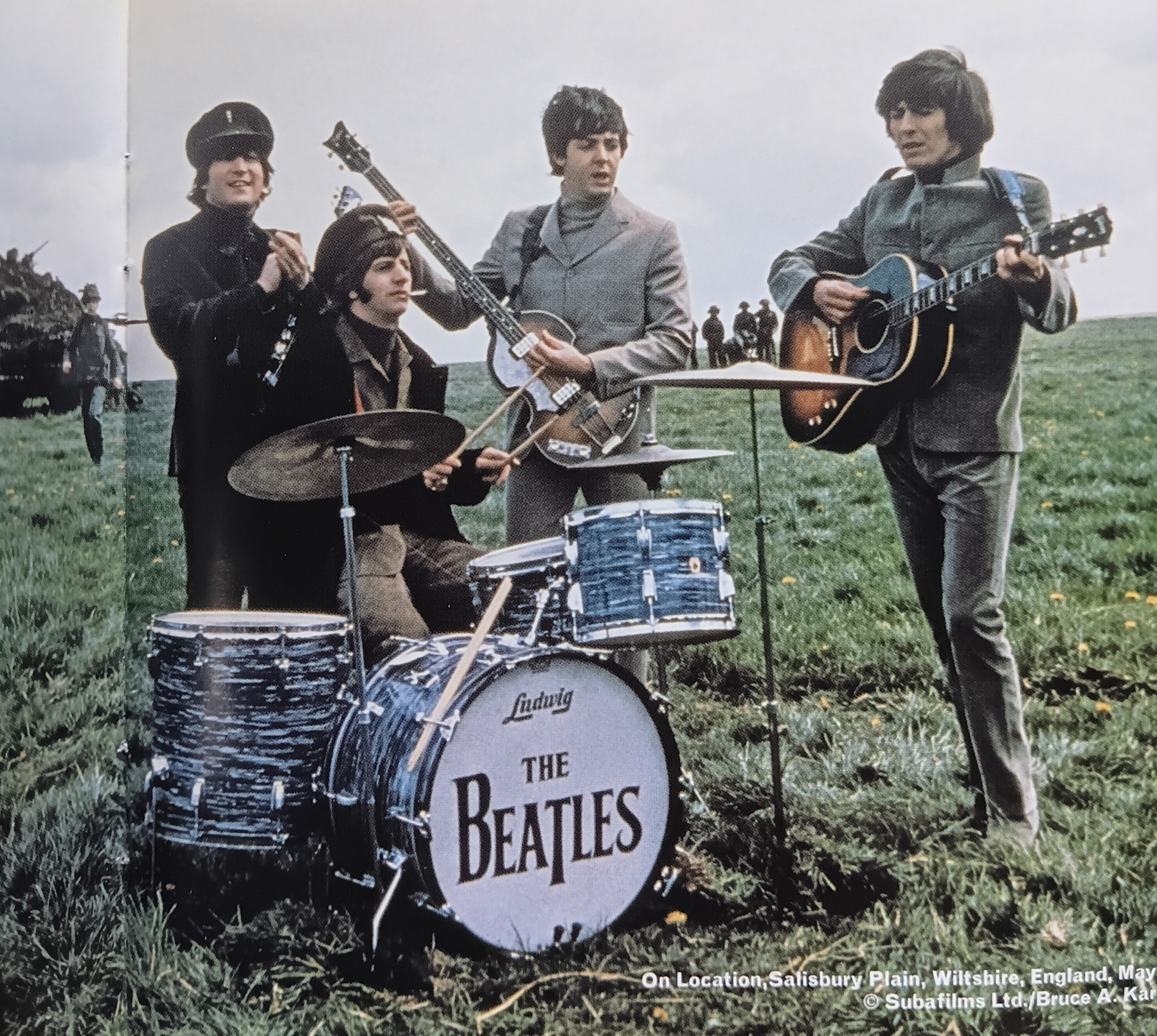

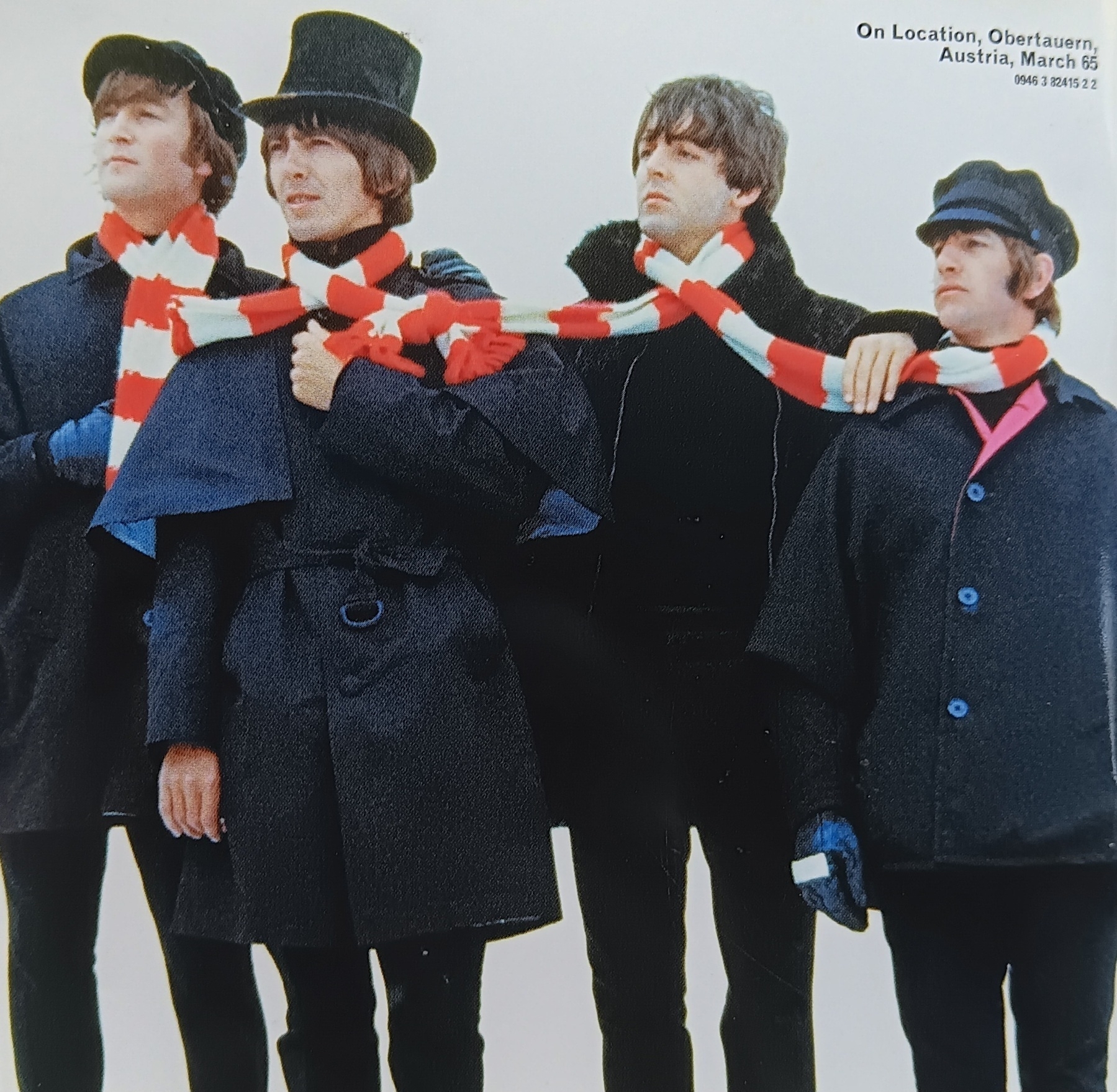

currently listening: Help! by the Beatles

rooftop